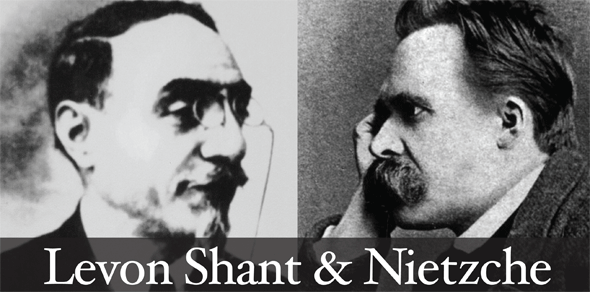

Levon Shant & Nietzche

By: Laila Babaeian

“What do savage tribes today take over first of all from the Europeans? Liquor and Christianity, the narcotics of Europe.” – Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

Liquor and Christianity are similar to the effect that they both have the ability to alter one’s state of mind and dull one’s senses. Where alcohol is able to intoxicate physically, as a result of the release of inhibitory chemicals in the brain, Christianity’s ability to intoxicate is of a wildly complex, counterintuitive, and entirely mental nature. Christianity is grounded on the assumption that the real world is attainable only after death, in the form of an afterlife, and is promised only to the pious. Piety entails the denial of worldly pleasures and refusal of the temptations of the present life. In essence, the present life is to be turned away from and treated merely as a means to an end—that end being admission to heaven. The concept of the afterlife is one that has greatly influenced the reality and behavior of many faithful Christians, argued Nietzsche, similarly to liquor and other “narcotics”.

Liquor and religion both appear in a different context for Nietzsche in his earlier work The Birth of Tragedy. In this work Nietzsche gives a historical explanation of the concept of Greek tragedy, and highlights the existence of a dichotomy in tragedy that includes both Dionysian and Apollonian influences. The Dionysian was named after Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, and signifies intoxication, irrationality, instinctual behavior, and ecstatic pleasure. The Apollonian, on the other hand, was named after Apollo who represents rationality, sobriety, and discipline. An ongoing struggle between these two influential elements is essential in preserving the balance necessary for the continuity of progress. Therefore, neither the Dionysian nor the Apollonian forces are to succeed in triumphing over the other. Though Christianity is not explicitly mentioned in this particular work, it shares in common with the Apollonian the fundamental principles of choosing rationality over instinct and a dedication to discipline in the face of life’s temptations. Similarly to the Apollonian, religion strongly antagonizes all of the objectives of the Dionysian.

These and many other ideas articulated by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche have influenced the works of various Armenian authors from the early twentieth century until the present. The work Hin Astvatsner by the playwright Levon Shant is one of such works. As the title suggests, the Dionysian–Apollonian dichotomy present in the play Hin Astvatsner corresponds to the clashing of the ancient gods with the Christian god. A young monk is torn between an Apollonian drive to devote himself entirely to what he believes to be rational teachings of Christianity, and a Dionysian longing to worship the ancient gods Vahagn and Anahit, who represent the visceral and worldly passions of war and love. After leading a monastic life of utter isolation from the outside world in an effort to ward off all worldly temptation, he falls in love with a girl whom he rescues from drowning. His faith is tested as he is consumed with delusions of the girl, in which she introduces him to the ancient gods that previously occupied the land his monastery is built on. The teachings of these gods encourage treating life as an end in and of itself rather than disconnecting from one’s life to contemplate the afterlife. He is intrigued by the revolutionary idea of living in fulfillment of the present and pursuing rather than renouncing one’s desires. The young monk’s balance is ultimately disturbed when the Dionysian forces win him over, leading to his tragic end by unintentional suicide.

The influence of Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy on Armenian thought is evident in Levon Shant’s play Hin Astvatsner, and may also be found in the writings of the famous Armenian poets Varuzhan and Avedik Isahakyan.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!