Armenian Youth Gather for 24 hours, Commemorating the 93rd Anniversary of Genocide

Thousands Protest Genocide Denial at AYF’s Turkish Consulate Protest

Hundreds Attend Burbank AYF Genocide Commemoration at City Hall

The Burden of Priviledge

In March of last year, I found myself in Armenia, walking to the AYF central office in Yerevan. There was a light snow coming down, the streets were filled with mud, and potholes were everywhere. As I walked down those streets, I could not help but compare my experience in Hayastan to the life I had in the States. I thought, “Man, I have it nice back home. A nice house, new car, and . . . hot water.” Being in Armenia, I realized just how much we take things for granted in the States, things which are actually luxuries in Armenia.

For instance, that morning I had waited for forty-five minutes in order for the water heater to turn on so I could take a hot shower. After the wait my choice for water was simply hot or cold, there was no in-between. A few more comparisons of this sort crossed my mind as I got closer to the office.

Finally, I walked in to find a young man sitting there reading a book. He asked me whom I was there to see and showed me the way to his office. As I walked into the building my friend greeted me and we immediately started talking about the upcoming ARF rallies that were to take place later on that day. We waited for a few minutes before our fellow youth steadily began showing up at the office. We all quickly mobilized and headed off to a political gathering that was taking place in one of the regions of Yerevan.

It was great seeing all of these young people climbing into the vans with their Armenian and ARF flags ready to go. It was especially impressive because it was not taking place on a Saturday or Sunday—it was Monday afternoon.

When we got to the rally, everyone went off to do his or her job. Some people set up the stage, others waived the flags, and others listened while the ARF candidates spoke. As I stood there I could not help but feel a sense of humbleness. My fellow Armenians humbled me, as they were doing what some of us do back in the States, but in their own homeland with much fewer resources to work with.

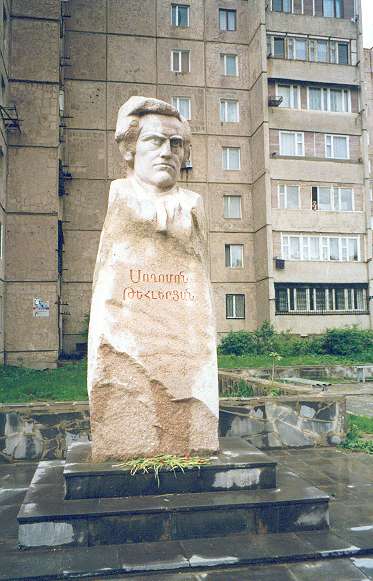

At the end, when the speeches ended and some folk dancers took to the stage, I remember looking around at the crowd, thinking how our people are a proud people, yet their state was not what it should be. The streets were filled with mud, everyone was dressed in gray and black, and the building weighed down upon the square. But, just then, I saw something that gave me hope. Behind the dancers on stage, there was the statue of Soghomon Tehlerian and there with it stood the spirit I am confident will lead to a brighter future.

On the drive back, all I could think of were the excuses. The excuses that we all have, the excuses that we all make about having work, having school, concentrating on our futures. The millions of excuses that we have given and, at times, heard; if not to someone else, then to ourselves. The end realization was that we in the US living in an abundance of “privilege.” Every one of us has a home, which, even if it may not be a mansion, still has running hot water every morning. Every one of us has a car and not once have any of us had to walk through a muddy street in order to get to school.

At the same time, every one of us has a burden: a “burden of privilege.” This is a burden that a person trying to survive does not have. We are privileged enough to have the financial means to attend universities and, as such, a special burden to use our skills to work for the survival and future of the Armenian people. We have the privilege of being citizens of a country where we are not persecuted for calling for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and it is our burden to work towards that recognition.

I can go on listing a million other privileges that I have discovered to have for myself, and I am sure you can find many more that you have. But recognizing your luxuries and privileges is not what is important. The real question is, what are you willing to do with the burden that comes with your privilege?

Kosovo Today, Karabakh Tomorrow?

By Tamar Shahabian

February 2008 was an important month in both the Balkans and the Caucasus. On February 17, Kosovo officially declared its independence from Serbia. Two days later, overshadowed by that news, Armenia held its presidential election, which was followed almost immediately by mass protests, street violence, political arrests and a nationally-declared state of emergency.

Kosovo’s self-proclaimed independence has also incited its fair share of dramatic turmoil. Serbs throughout the Balkan region are angry and humiliated; and at the time of this writing, fewer than 30 countries out of 192 member states of the UN have formally recognized Kosovo’s declaration – hardly a majority. Serbia, Russia and a handful of European countries have been outspoken about their belief that recognizing Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence is tantamount to trouncing the international laws that govern matters of state sovereignty. They are worried about their own unhappy minorities getting ideas or gaining momentum for separatist quests. There has been much talk about whether a ‘Kosovo precedent’ has been created and what implications that might have for self-determination movements the world over.

They are right to worry. The manner in which Kosovo became a state was a historical event and historical events set precedents, period. Moreover, secessionist states such as Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, Palestine, Somaliland, and Western Sahara have much more in common with Kosovo than the US or UN want us to believe. Like Kosovar Albanians, citizens of many aspiring states have suffered discrimination, pograms and ethnic cleansing at the hands of their ‘parent states.’ They have responded by taking political measures to separate themselves from those national leaderships that failed to protect or include them; they have built democratic institutions of their own; and, over time, they have become functioning entities. After so many years of self-rule, it is not only unjust, but unrealistic to expect them to re-integrate into the states which forced their separation in the first place.

To be sure, the sheer amount of resources and attention that has been devoted to Kosovo by the international community cannot be rivalled by the other aspiring states; in this sense, Kosovo is unique. No other comparable movements have received the extent of military, economic or political support enjoyed by the Kosovars. Political circumstances have been the determining factor in which self-determination movements become valid in the eyes of the international community. But the way external actors regard Kosovo is not the only thing that matters. The internal drive and passion of the Kosovar Albanians to be free to govern themselves and exercise the same right of self-determination that all ‘peoples’ are entitled to is the same drive and passion which motivates other such movements.

Indeed, the Albanians of Kosovo and the Armenians of Karabakh base their statehood aspirations on the same principle: the right of self-determination, which was first enshrined by the UN Charter in 1945 and reinforced in subsequent texts which still form the basis of international law on the issue of national territory. The fact that Kosovo’s plight has received unequivocally more attention than Karabakh’s does not change the fact that both movements are legitimate for the same reasons.

Still, the outcomes have played out differently as Kosovo has now achieved its goal of independence – to the credit of the US, most of Western Europe, and the UN rather than Priština, necessarily. In other words, Kosovo’s self-proclaimed independence would not have mattered so much to anyone but the Serbs if it were not for the acceptance of that proclamation by other countries, including the world powers (with the notable exceptions of Russia and China). To use the words of New School University professor, Anna DiLellio, independence is not so much declared as recognized – meaning that a claim of independence is not legitimate unless or until others confirm the legitimacy of the claim.

Armenians are well aware of this political realism; Karabakh made its own declaration of independence in 1991 but still no country in the world has recognized it as a sovereign state. So how real is the claim? Isn’t the essence of self-determination that peoples should be the determinants of their own fate? Why should the rest of the world disregard their voices? Why should we force them to be part of a state they want nothing to do with? Whose right is it to say that they, the very people inhabiting the land, should not have the final say in how that land is governed? Is that not what democracy means at its core?

Yes, it is, but only in principle. In the real world, states will choose whether to recognize Kosovo based on political considerations such as their own domestic state of affairs, positions of their allies, and economic matters. Nations will not base their policy towards Kosovo on principle, or even really consider whether the Albanians there have a just claim to independence. We live in a state-centric system; by definition, it is in the national interest of countries to discourage and dismantle self-determination movements since they threaten to change the lines on the world map from which states derive their authority.

Thus, the outcome of the Kosovo situation is the exception and not the rule. In principle, it is a precedent, but in practice, it may be an anomaly.

So what then is the relevance of Kosovo to Karabakh? My only answer is this: the exceptional international attention that has been and will continue to be devoted to Kosovo’s independence may be able to serve as a starting point for launching a more widespread dialogue on the issue of national self-determination. If nothing else, perhaps the simple fact that a decisive outcome to the Kosovo situation has finally been reached will give hope to other peoples in similar situations that the deadlock need not last forever.

Turkey and Sudan: A Genocidal Tandem

While other countries in the world have criticized and increasingly distanced themselves from the Sudanese regime and its atrocities in Darfur, the Turkish government has been going out of its way to forge ever-closer ties with its genocidal apprentice in Khartoum.

While other countries in the world have criticized and increasingly distanced themselves from the Sudanese regime and its atrocities in Darfur, the Turkish government has been going out of its way to forge ever-closer ties with its genocidal apprentice in Khartoum.

This past January, Turkey’s president, Abdullah Gul, hosted an extravagant three-day visit for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. This was the second such official trip from Sudan to Turkey at the presidential level. During his stay, Bashir was treated to an exclusive state dinner at the Turkish presidential palace, met with several top level officials, and attended a Turkish-Sudanese business meeting held by the Turkish Foreign Economic Relations Board (DEIK) in Istanbul.

This latest trip is only the most recent manifestation of a Turkish affinity for Sudan that has been steadily growing in line with an escalation of violence in Darfur since 2003.

As has been well documented, the Darfur region of Sudan has been subject to a systematic campaign of murder, looting, rape and pillaging, carried out mainly by a government-sponsored militia known as the Janjaweed. According to international human rights groups, this campaign has already resulted in the deaths of over 400,000 people and the displacement of 2.5 million from their homes, in what the United States has officially described as genocide.

While the rest of the world has marginalized Sudan and called for an end to its crimes in Darfur, the Turkish government has proceeded to turn this country into its largest trading partner in Africa. The volume of trade between Ankara and Khartoum shot up from $48 million in 2002 to $220 million in 2006—an increase that took place during the same period when Sudan was intensifying its killings in Darfur. Turkey hopes to develop these trade links even further in the future, with one of the stated goals of the above-mentioned DEIK meeting being to boost levels of trade to $1 billion.

As a country that has been outcast in the international community, especially in the West, Sudan very much values Turkey as an economic and political partner. As al-Bashir stated during his remarks at the DEIK meeting, “Sudanese businessmen do not only want to emerge in the Turkish market, but also to use it as a passage to European and other international markets.” In turn, Turkey hopes to benefit economically from Sudan’s potential in sectors such as oil, cotton, industry, and services. There have also been reports that the Turkish Defense Ministry is currently looking into supplying Sudan’s deadly demand for weapons.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the country responsible for the first genocide of the twentieth century has no qualms about building a strong strategic relationship with the country now carrying out the first genocide of the twenty-first century. Indeed, not only is Turkey rewarding Sudan for its inhumanity by filling up its coffers and helping it access markets in Europe, but we also see it actively taking part in Khartoum’s shameless campaign of genocide denial.

In a January 20 interview, prior to al-Bashir’s visit to Turkey, President Gul told the Sudan News Agency that Turkey is in “solidarity” with Sudan and warned against any “foreign intervention” over Darfur aimed at breaking “the unity of Sudan.” He later dismissed calls for putting pressure on al-Bashir to end the atrocities in Darfur by claiming what is happening there is a “humanitarian tragedy” that “stems from poverty and environmental conditions.” Gul’s colleague Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, also joined in on the denial when he stated in March 2007, “I do not believe that there has been assimilation of a genocide in Darfur. In any case, the verses of the Koran reject tribalism and clans.”

In fact, when one takes a close look at Sudan’s method of genocide and its subsequent denial, we see that they are doing nothing more than taking a page out of Turkey’s playbook (see Chart A for Sudan’s almost word for word use of Ankara’s genocide denial techniques). The fact that Turkey committed genocide and remains unpunished for so long has surely emboldened the regime in Khartoum to carry out similar policies in Darfur without fear of serious retribution. Like Hitler, al-Bashir must be thinking to himself, “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

Indeed, Sudanese officials have repeatedly stated their lauding admiration for Turkey as “a model for Sudan” and desire to “want to benefit from Turkey’s experiences.” They have also sought to market themselves to the world in an identical manner, with Sudan describing itself as a “bridge between Arabic and African nations,” much like Ankara claims itself to be a bridge between Europe and Asia.

Thus, it is clear that the Sudanese regime is trying to follow in Turkey’s footsteps. This adds further proof to the fact that giving in to the Turkish denial machine makes the world a more dangerous place. As long as Turkey does not own up to the crimes it has committed (and is aided in this process by officials in the US), it will continue to serve as a model for governments such as that of Khartoum who seek to get away with slaughtering an entire group of people.

In the words of Mark Hanis, founder and director of the Genocide Intervention Network, “Increased cooperation between the two countries [Turkey and Sudan] serves to highlight the connections between genocides of the past and those of the present . . . The continued denial of the Armenian Genocide sends the wrong message to Sudan and those who would commit genocide in the future.”

If we want to stop the cycle of genocide today and prevent future atrocities, we have to start by speaking truthfully about the genocides of the past. In this way, recognizing the Armenian Genocide is not a historical issue but, rather, a very current one with real world consequences for peace today.

Turkey and Sudan: Comparative Genocide Denial

Turkey |

Sudan |

“Our culture does not allow genocide” |

|

| Recep Tayyip Erdogan (National Press Club, 11/5/07): “In fact, our values do not allow our people to commit genocide. It does not allow it and there is no such thing as a genocide.” | Omar al-Bashir (MSNBC Interview with Ann Curry, 3/19/07): “Villages were burned, and people were killed, but it is not in the Sudanese culture or people of Darfur to rape. It doesn’t exist. We don’t have it.” |

“The victims rebelled/foreign powers are to blame” |

|

| Recep Tayyip Erdogan (National Press Club, 11/5/07): “This was about the time when there was rebellion in different parts of the empire. But given the context of the time and the events that took place at that time, there was provocation by some other countries and the Armenians became part of the rebellion in those years.” | Omar al-Bashir (Asharq Alawsat Interview, 2/17/07): “There is a rebellion problem in Darfur, and it is the duty of a government in any state to fight the rebellion. When war takes place, civilian victims fall, and this has been exaggerated.”

Omar al-Bashir (Reuters, 1/22/08): “The people who really commit murders in Darfur are receiving help from Europe and others.” |

“It’s deportation and war, not genocide” |

|

| Recep Tayyip Erdogan (National Press Club, 11/5/07): “I’ll tell you something now. There is no [Armenian] genocide here. What took place was called deportation. Because that was a very difficult time. It was the time of war, in 1915.” | Omar al-Bashir (MSNBC Interview with Ann Curry, 3/19/07): “The geographic displacement of people that took place in Darfur is due to the fight in Darfur. The citizen has to move out of the fighting areas to a place of security, seeking peace and security. . . yes, people were killed but not as much – it’s a war! |