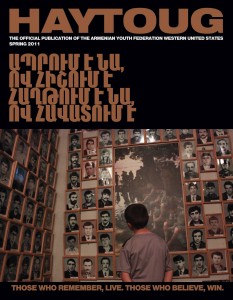

Ruben Hakhverdyan

On February 13, 2011 the AYF brought legendary singer and poet, Ruben Hakhverdyan, to downtown Los Angeles’ famous Orpheum Theatre for a one-night only performance. Nearly 2000 fans crowded into the halls of the Theatre for what was one of Ruben’s largest and most memorable performances.

A few days after the concert, we had the chance to sit down with Ruben for an exclusive interview with Haytoug, covering everything from the concert to his music to his thoughts on culture and politics.

HAYTOUG: It’s been six years since your last visit to Los Angeles. How does it feel to be back and what are your impressions of life here?

RUBEN HAKHVERDYAN: You know, I haven’t really gotten out much since coming here. I just visited a few friends so I can’t really give you much of any impression. I came here to sing, which is my job, and then I’ll be going back home.

I can’t really comment on how things are here because I feel one has to actually live here to really understand both the positives and negatives. Like I said, my job is to sing and I really haven’t gone out too much.

H: Is there a difference between performing in a Diaspora community like Los Angeles as opposed to in Armenia?

R.H.: None whatsoever. It has never made a difference for me where I’m performing. I have even sung in France for a French audience and it made no difference at all. They received me with the same warm welcome. The translations were displayed on the screen while I performed so they understood the meaning of my songs.

I have sung for the Czechs in the Czech Republic, for Serbs in Serbia, and so on. For me, it doesn’t matter who is in the audience. The most important thing is to make sure that, whenever I perform, the audience is left pleased.

H: At the concert here in Los Angeles, you sang a song you mentioned you had written when you were 18. Can you tell us a little about when you began writing these songs and what motivated you to become a singer-song writer?

R.H.: When I was young, the guitar was a very popular instrument and many of us back then wanted to be like our favorite bands of the time. We looked up to the Beatles, or solo artists like Johnny Cash, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor and other famous—mostly American— singers. These artists were some of my favorites and they were my first inspirations.

I started when I was around 18 years old, learning little by little here and there. We all learned something from each other as friends and then took it from there.

H: During your performance, you also referred several times to the bandukths, those Armenians who continue to leave their homeland for lives abroad.

R.H.: Yes, I touch upon that theme a lot in my music but I usually don’t sing about it during my concerts. You know why? Because it is almost as if emigration has become our nation’s destiny, especially these last couple of years.

H: What do you think are the main reasons for this emigration?

H: What do you think are the main reasons for this emigration?

R.H.: People leave Armenia because they can’t find work there, because life is not very pleasant. It has to do with social injustice and economic hopelessness. Another key reason is that the people have been disappointed by all three ruling regimes in Armenia since independence. They feel as if all three administrations came to power only to rob their own people.

H: There are some who feel it is this generation’s responsibility to go back to Armenia in order to be in the homeland and improve the situation. What do you feel about the concept of repatriation and Tebi Yergir?

R.H.: In every nation, there is a segment driven by ideals. Usually, these people make up around 5-10% of the population. Being ideological is a good thing if your convictions are truly your own, not something strained around your neck from above. It is positive because it makes you stand out from the rest of the crowd that simply follows a preset path.

I consider myself closely associated with, and have many friends within, the ARF-Dashnakstutsyun. Even there, however, there aren’t that many individual thinkers. I would say again, in my opinion, they make up about 5-10% within the party.

I place the most importance on the rank and file members and supporters of the ARF, including especially the youth, because they are searching for their national roots within this party—nothing else.

I don’t give too much importance to the leadership because it can always change. The ideals of the party, on the other hand, always remain the same.

From what I’ve seen, the most patriotic youth I’ve come across belong to this party.

H: While you’ve shown support for the ideology of the ARF, you’ve also expressed disappointment with the party. Could you explain what it is exactly that has disappointed you?

R.H.: For me, it was them joining and leaving the coalition. I was opposed to it from the very beginning. But since I’m not a member of the party, it is not my business to meddle. Nevertheless, they should never have joined the coalition knowing who they were going to be partners with.

H: Getting back to your music, you spoke during the concert about the state of Armenian music, criticizing the lack of art and meaning today. What do you think the implications of this are for Armenian culture?

R.H.: There are only a few artists today who belong to a narrow genre I call “poetic music,” where the lyrics actually have meaning. Now, if you look at popular artists today who fill up stadiums, most of their lyrics have no meaning. In a lot of cases, they steal their ideas from one place or another and use artificial melodies.

But I actually don’t blame the artists who sing these foolish songs. It’s the fault of the people who want to hear that type of music. It’s the consumer’s fault, not the producer’s—just like the bribe-giver is as guilty as the bribe-taker. I believe our society is really quite backwards in this regard. My only hope is our youth because what we need are new minds and new thinkers who can present new ideas completely different from what is the norm today.

H: What role do you see music having in the larger context of preserving Armenian language and culture in the 21st century?

H: What role do you see music having in the larger context of preserving Armenian language and culture in the 21st century?

R.H.: My art is a bit different in the sense of preservation. For example, I tell the story of my generation. I paint a picture in time of the Armenia of my era. I sing this type of music, not so people won’t be disappointed in our language which is our fatherland, but so they will return to our language lovingly. Because our fatherland is indeed our language.

For instance, for your generation, your fatherland is not necessarily Armenia because you don’t live there. Armenia for you is the Armenian language. So, for me, the Armenian language holds more importance than, say, paintings of scenery and mountains or rivers.

H: You’ve said both in interviews and alluded to in your songs that what we see today in Armenia is the continuation of the Soviet experience. That the new leaders are following in the footsteps of the old. Why do you think this is?

R.H.: It’s not the fault of the leaders themselves. Most of them lived the majority of their lives under the Soviet regime and that mentality has been rooted deeply within them. That’s why I say we need new thinkers and new plans. The older ones need to be forgotten because they are the same Communists as before. There is no difference with the past. In fact, you could say leaders today are actually worse. Communists who have no rules or laws can steal as much as they want.

H: Do you think the dashing of people’s hopes and aspirations after independence has contributed to this cycle and the disillusionment of people toward change?

R.H.: That hope during independence died because we didn’t have any truly national figures. Those who we did have went on to turn patriotism into a business for themselves, with each one concerned only with filling their own stomachs. We don’t have selfless leaders; we don’t have national figures. That’s the most painful thing about today.

H: Whether it’s your songs, your concerts, or your interviews, you always seem to speak your mind without any fear. What makes you so outspoken?

R.H.: I speak openly like this because I feel an obligation towards our youth. I feel obliged to encourage them to think and speak freely, because the true concept of a homeland requires having such freedoms. Why would I be afraid to speak out?

During the Soviet times, I spoke against the Communists and, of course, there were pressures placed on me. They wouldn’t play my songs or allow me to sing. During Levon’s [Ter Petrosyan] administration, I spoke against him, too; during Robert’s [Kocharyan] administration, I spoke against his many mistakes; and during Serzh’s [Sargsyan] administration I speak up against his. It is very important to think freely and be honest, first and foremost with yourself.

H: Where do you see yourself and your music heading in the future?

R.H.: I never think about that. I haven’t thought about that nor do I plan to…

H: But what can people expect from you?

R.H.: From me? Nothing good (laughs) . . . I don’t know. You can expect something that you never expected…