Ces’t La Vie

A short story by Arin L. Shane

There were two stacks of newspapers at any newsstand in the small, seaside town of La Vie. One was the La Vie Times and the other was the Press de Vie. On any given day, one newspaper outsold the other by a small number of copies. In large, this was due to the appeal of the articles written by each of the newspapers’ famous political columnists. The La Vie Times held in great regard their young writer Claude Dubois as equally as the Press de Vie held in regard their own columnist, Edouard Guillotine. It was once a week from the years of 1909 to 1910 that each would have their opinions printed in their papers. The material they wrote was deathly contradicting to one another. The time was approaching for the town of La Vie to vote for a new representative; Charles Leroy, whom Guillotine fended for, and Benjamin Moreau, who Claude greatly admired. The two writers both expressed their ideas and opinions with pleasure and passion; and certain weeks Guillotine’s article would be praised more than Claude’s, and sometimes the opposite. Of their many similarities, both worked from home, and both shared a particular dislike for one another.

One morning, Claude had returned from his trip to the La Vie Times building to turn in his latest work. He’d just taken off his hat and coat when a knock came at the door. He opened it and in came Bernadette, a long time friend of the writer “Bernadette,” said Claude, “what a surprise—” Bernadette whisked by without a greeting.

“A pleasant one, I hope,” she said, with an uneasiness in her tone indicating there was an important issue at hand.

“As always,” said Claude and the two walked to the middle of the small apartment where Bernadette sat and Claude went off to the small kitchen to bring pastries and coffee. He placed them on a small table between the two chairs and sat down.

“To what may I owe this visit, my dear?”

“Need I a reason to visit an old friend—?” Claude raised his brow. “Well if you insist I need a reason, yes, I do have one. Alarming, and you must take it seriously; you know how you have a problem with that—”

“I do not. Go on then,” he said and, with a smile on his face, bit an éclair. Bernadette didn’t speak, but pulled out a folded up newspaper from her purse and held it up to Claude’s face, He took the copy from her white-gloved hand and opened it.

It read: “La Vie Times columnist Claude Dubois seems to be swinging the votes with his weekly articles in the paper….”

Claude continued but Bernadette pulled the paper from out of his hands.

“That’s not very nice you know,” he said.

“What’s not nice is that you’re mingling with politics. And if you’re not a politician, it’s not your place and you know that well and yet you keep writing these columns and it’s—not right. For you to write the things you do, and for a newspaper in Paris to say this about you, it’s dangerous and you know it.” She sank back into her chair and sighed.

“And why is this all an issue for you? I’m doing my job. Besides, you know as well as anyone else that the politics isn’t what I truly care about. To be in newspapers, Bernadette, it’s my dream. It’s my work—”

“Doing your job doesn’t mean writing the way you do. You write about politics in such a stern way in this feud and you seek fame doing it. Look at writers and artists of this day and the past. Famous were many and they did not have to create terrible and vile works to achieve the feats they did. Why must you be so hesitant to create pleasant writings?” She grabbed a pastry and sank even deep into her chair.

“It’s not simply a feud, dear Bernadette, it’s a battle, between two skilled opponents. Our weapons? The pen, though I have been trying to get my hands on the latest typewriter from America. A new machine. With a pushing of buttons, one will have a sentence in seconds…. It is true; pleasant works would evoke less tension in the town, but my dear, people have an uncanny desire to see the dark, live it, be a part of it. The dangerous is what we all seek inside, the thrill. Either way, you mustn’t worry, I’ve it all under control.”

“Then I take you expected that what you wrote would change the votes around the whole town?”

“Ah yes,” mumbled Claude, “well I didn’t think of that happening—but this just means I’m winning against that ancient sac of bones.” Bernadette wiped her mouth of crème and put her hands together on her lap.

“Yes well, one more thing I wanted to tell you. See, they’ve been writing about Guillotine as well. He’s shifting the votes just as much as you. The way I see it, you’re both in danger, so perhaps—”

“Let that old man be in danger. All I have to do is write better than he, and I’ll be back at the top, like I was until he decided to move into La Vie. You’ll see, dear, I’ll have this whole town in my hands when I’m through writing.” Bernadette quickly rose from her seat and drove her heal into Claude’s foot.

“Sure, you fool, go against everything I say right in front of me. Keep this up and one of you will get hurt, or worse you’ll have to answer to me. Goodbye,” she said and marched out of the apartment. She shut the door behind her and chips of paint fell to the ground. Claude sniggered and limped to his writing table where he began creating his next article.

Many streets and shops away, on the other side of La Vie, lived Edouard Guillotine, a slender old man with a long, black goatee and a damp air around him. His accommodations were larger than most in the town; his home was full of long hallways which housed rooms engulfed in dust with a few chairs thrown around. The walls of empty corridors were spotted by places pictures once hung and only the faintest light was ever lit. His writing room looked over his front garden, which had hedges not manicured for years and grass as green as could be. Earlier this afternoon, Edouard had read of how his writing and fame had reached Paris and sooner or later, the whole of France would know of his name. He also read of how Claude Dubois was also reaching ears as far as Paris. The rivalry, Guillotine thought, was in vain, for in the end, there was no chance of Claude writing something so much more praised than his own work.

Guillotine stood alone in his office which was burgundy in color, and watched with his hands behind him as people walked the streets and an occasional leaf, still green, flew in the light wind. The sunlight shined into the room, dimmed and dispersed by the chiffons, drapes and curtains sun bleached. He sighed, then slowly walked to his typewriter, the latest from America, and began to write. At night, he appeared much like a ghost, covered in a pearly light from the moon. He seldom slept most evenings, but only walked the halls of his home. And when morning came, he would sometimes walk around the nearest block or two, then return home to read or work.

After the morning, at around noon, Claude finished the final draft of his new column on the silliness of Charles Leroy and those who followed him, particularly Edouard Guillotine, “a man with much to say, but sadly not enough worth in his speech to match.” Claude slipped into his coat, put on his hat, and began his walk to the La Vie Times building near town square. He passed by many news stands on his way and was often greeted, and always smiled when he saw that a stack of the La Vie Times was lower than a stack of the Press de Vie. A wonderful sun hung over the town and the waves were never too far so that their shanties could not be heard. Seagulls flew overhead. Returning home, he wished he’d taken enough money to buy groceries, so all he purchased was a bottle of wine and a loaf of bread.

The following Sunday, both Claude’s and Guillotine’s articles were printed in their respective newspapers. Guillotine’s ended as such:

“Anyone who ambles about in favor of Benjamin Moreau

should reconsider the circumstances, particularly those who seem so compelled that they find the need to write about him and praise him. We mustn’t forget people who write such bias works of such bias people are unreliable, and are perhaps in somewhat of a need of a course correction. Bonne vie to all; I will be writing soon again.”

And Claude’s:

“I do agree that Charles Leroy is a fine man, but do no be tricked into thinking he is a fine politician, or even decent, when compared to Benjamin Moreau. Must we think so hard on something so simple? and by such deep thought be blinded by the clear answer that stands before us? Perhaps those who do, particularly the slender type, with small glasses who type away on fangled machines should open their eyes to the truth and not wallow in their bias. Until next week, my dear readers, Claude Dubois.”

Garbage, thought Mr. Guillotine. How could they publish such lies for all to see? I wouldn’t be surprised if this has reached Paris already. The old man walked to his window and stared out as he often did during different hours of the day. Today he would not write, for the sun seemed odd and there wasn’t enough wine to get him through it. Today he would only read, and remember, and do his best to not pay any attention to news of the hideously bias, extremely famous writer, Mr. Claude Dubois.

Claude himself was out celebrating his latest and favorite publication with his darling Bernadette. She spoke little, though he could not stop speaking away of how he believed he’d completely destroyed “the old bag of cracking bones and that typing machine of his.” The two ate by a place near the sea where a wonderful café 24 SUMMER hung over huge cliffs and seagulls nested on pointed rocks. The sun was just a few hours away from dipping back into the ocean to bring night along to the town of La Vie, and Bernadette felt it was time to go home. Claude agreed, and, placing her coat over her shoulders and giving her a kiss as she reluctantly allowed, the two parted ways on Mouette Avenue and each went to their separate houses.

The most shocking event occurred in the days following. At all the newsstands in the town, the La Vie Times was outselling the Press de Vie by not just a few copies, but rather stacks and stacks. Readers were demanding more copies, and demanding that those copies had more of Mr. Claude Dubois’ columns in them. His employers agreed to double his payment for each article, and Claude could not have been more happy for he was now receiving optimum recognition and a fine pay with three publications a week. On the contrary, Edouard Guillotine was struggling to aid the Press de Vie return to its previous popularity. Alas, his efforts were to little avail, for the Press was barely selling enough copies to remain in print and a great deal of the blame was put on Guillotine .

It was nearly sunset and Edouard was out at the beach standing in the wet sand where the water would ease up to him but never come to surround his feet. Then it would ebb back to the vast sea. Wearing mostly black, he looked over his spectacles to the orange horizon. Pink clouds spanned over the water with the rays of the sun, covering the sky. A shimmering road of light went over the sea from the sun to the docks miles from where Edouard was. No shimmering road of light led to him. The sun soon disappeared and Edouard began walking back to his home. The walk was long, longer than usual, and turning onto Corrotto Road, he stood before his home. Only, his home was not there. His hedges were not there. No neighbors were around. Edouard found himself on the wrong street. With a sigh and a smile, he walked down a few blocks, and again found himself standing before a house that was not his.

He could not find his home. He searched the roads, and often became lost.

It was not until ten in the evening, after hours of walking, that Edouard Guillotine found his home, and upon entering, went straight to bed.

In one of his new, weekday articles, Claude wrote of his content and pleasure toward the fact that Benjamin Moreau was rising in the polls and it seemed that he was ascending to the position of representative. While Claude’s career blossomed with humble prosperity, Edouard Guillotine still struggled to win the appeal of his audience once more. He began to spend more and more time on his typewriter; every second there was a clack from the keys and red wine, looking more like blood than the drink itself, rippled beside him. Columns were published, but Guillotine continued to write with no light shining on his work. There came a time soon after where the clacking of the typewriter lost its rhythm and often the wine spilled onto the table and dripped to the floor. He began producing irrelevant columns; articles that had dozens of topics but none of which had anything to do with politics. Only two more publications were tolerated, after which the Press de Vie handed him his final payment, and wished him a happy career.

Claude remained in his old apartment, only he chose more lavish furnishings and finer china. Together with Bernadette, the two sat in his home in solemn conversation.

“You mustn’t think you had no hand in this,” said Benradette.

“Now I’ve caused the old man’s mind to crumble? He had it coming to him for years. He had plenty of time to back out of this project—”

“Doesn’t matter what he chose to do; You know what you wrote, and know it moved him just as much as it did your readers. Foolish to deny….” Claude was silent, but he then spoke:

“Was it Newton that spoke of how the only reason he could see far was if he were standing on the shoulders of giants? I believe it was him…yes….” He slipped into thought, looking out the window to a sunny day.

“He was a man just as dignified and worthy as you, and a writer just as famous and read as you, too. You can’t deny that, and I know you don’t darling. I’ll be going now, Claude, I’ll speak with you later.” Bernadette rose from the chair and walked to the door, and opening it, was soon gone down the hall. Claude’s deadline for a finished draft was upcoming, as his articles appeared more often. So he walked slowly to his writing desk with his hands in his pockets, and, sitting down, picked up his pen and quickly began running it over the paper. Writing.

The last column Claude ever wrote of Monsieur Edouard Guillotine appeared in the following weeks, and read as follows:

“Methods and traditions have come and gone, but the way of

a writer has remained honest and truthful to its origin. Particularly to

we who write of our opinions. We place ourselves, our true thoughts

and true beings out before all. We are judged; sometimes favorably

and sometimes not. However, it is not for these judgments which

we write, it is to continue the life of our civilizations which have for

so long lived upon it, a part of it. Our earth is merely two billion

souls and two billion perspectives. And it is these strong opinions

that allow us to endure through what an overgrowth of societal

influence poses on those who prefer to write their minds. We are

the peoples we are only because there have been so many brave

peoples before us, many no longer present, who chose to fight and

cope, and build a civilization upon which ours rests today. Without

that very bedrock of those who have gone before us, we would go

as they, only with no purpose to our existence. Such a bedrock I

dealt with, and feuded with, for some areas of it were not perfect.

Though, it is those imperfections that allow us to excel today, for

with perfection, we become still, a cloud that never moves in a sky

that never darkens. Though few have been able to gaze down the

vistas and sweeping fields that I have seen in my short time, there

is no doubt in my mind that such wonderful, open places would

not be if it weren’t for the giants whose shoulders we stand on,

and for those who ever dared to change what was around them

instead of them themselves being eroded by the times. And though

the wind-swept souls and subtle hearts, that have not survived an

equitable time, toll in their graves with unrest, we who change that

which is around us with the word, my dear God, we are the ones

who set them free, and in their gratitude, the passed people give us

their bodies so that our world shall not die. And so that all continues

from the previous stone left standing. Yours truly, Claude Dubois.”

Arin L. Shane is a student at Providence High School. His writings and short stories have been featured in the Los Angeles Times ‘Kids Reading Room’, among others.

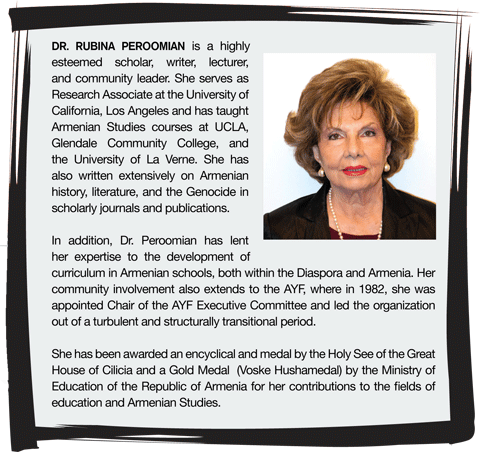

Interview with Dr. Rubina Peroomian: The Power of The Pen

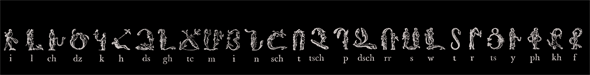

Haytoug: Armenians have long took pride in education and having an alphabet that is now over 1,600 years old. Given this legacy, how big of a role would you say the written word and literature has actually had on shaping the destiny and identity of the Armenian people?

Rubina Peroomian: Yes, we are proud of our culture, our heritage and our 1600-year-old alphabet. We are proud of the rich literary output that made the fifth century the Golden Age and the tenth and eleventh centuries the Silver Age of Armenian literature.

Yes, education has always been one of the key values upheld in Armenian families. But this consciousness was germinated, expounded and disseminated by the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance movement which was launched to enlighten and educate the Armenian masses, disseminate religious and cultural values, and propagate ideas of modernity. Before then, these values were esteemed and perpetuated by a relatively small class of men and women—which included the clergy, the ruling class, the nobility and the intellectuals—while the masses lived in ignorance and poverty under the yoke of foreign domination, deprived of basic human rights.

What shaped the destiny and the identity of the Armenian people, in other words, what sustained their survival throughout their turbulent history, was their devotion to Christianity in the midst of the encroaching Muslim world and a subconscious effort to maintain and perpetuate their ethnic origin, traditions and language. An influential factor here may have been the spoken word and not the written word or literature.

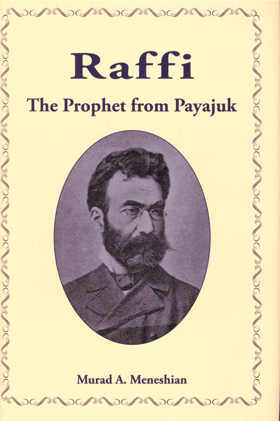

H: It is often said that the cultural renaissance of the Zartonk (Awakening) period of the 19th century gave birth to the Armenian revolutionary movement. In what ways exactly did writers like Mikael Nalbandyan, Khatchadour Abovian, Raffi and others spur Armenians to stand up for their liberation? Weren’t the material conditions experienced by Armenians in the Ottoman Empire alone enough to make them want to resist their oppression?

R.P.: The political awakening was the final phase of the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance which began with an Enlightenment movement, the establishment of a network of modern schools, the periodical press, and the modernization of the language with the replacement of Grabar (which was unintelligible to the masses) by two literary languages closer to the dominant vernaculars. Through these vehicles the Armenian intelligentsia were able to propagate the Renaissance ideology which was, in essence, the aspiration to live the life that all humankind deserved to live. And the model, or the source of inspiration, was not so much the European example but the glory of the Armenian past, drenched with an insatiable love of liberty and justice and bolstered by a rich culture that Armenians can be proud of. The Armenian masses needed to become conscious of their own deplorable situation before they were able to aspire to a better future. It was during this period that the written word and the literature created by the Renaissance writers, some of whom you mentioned, assumed the role of reshaping the Armenian identity which had been buried in obscurity and the darkness of centuries of subjugation. This literature cultivated the Armenians’ will to stand up and fight for their rights and take their destiny into their own hands. Call it tendentious or committed literature if you will, let some literary critics campaign against it, but the literature of the Zartonk period did the job. This literature can be considered the realization of the theory of “reflect and control,” to use Melvin J. Vincent’s expression. It presented Armenian life as it was in its ugliest aspects, and at the same time it propagated and cultivated what was desirable, what was worth fighting for, in the reader’s mind. In other words, the Renaissance artists not only held up a mirror to reflect life as it was, they presented a model of what it should be. These models created characters, heroes of national dimensions who acquired flesh and blood in the forthcoming national struggle for liberation.

R.P.: The political awakening was the final phase of the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance which began with an Enlightenment movement, the establishment of a network of modern schools, the periodical press, and the modernization of the language with the replacement of Grabar (which was unintelligible to the masses) by two literary languages closer to the dominant vernaculars. Through these vehicles the Armenian intelligentsia were able to propagate the Renaissance ideology which was, in essence, the aspiration to live the life that all humankind deserved to live. And the model, or the source of inspiration, was not so much the European example but the glory of the Armenian past, drenched with an insatiable love of liberty and justice and bolstered by a rich culture that Armenians can be proud of. The Armenian masses needed to become conscious of their own deplorable situation before they were able to aspire to a better future. It was during this period that the written word and the literature created by the Renaissance writers, some of whom you mentioned, assumed the role of reshaping the Armenian identity which had been buried in obscurity and the darkness of centuries of subjugation. This literature cultivated the Armenians’ will to stand up and fight for their rights and take their destiny into their own hands. Call it tendentious or committed literature if you will, let some literary critics campaign against it, but the literature of the Zartonk period did the job. This literature can be considered the realization of the theory of “reflect and control,” to use Melvin J. Vincent’s expression. It presented Armenian life as it was in its ugliest aspects, and at the same time it propagated and cultivated what was desirable, what was worth fighting for, in the reader’s mind. In other words, the Renaissance artists not only held up a mirror to reflect life as it was, they presented a model of what it should be. These models created characters, heroes of national dimensions who acquired flesh and blood in the forthcoming national struggle for liberation.

The revolutionary movement was a byproduct of the Renaissance, as was the formation of the Armenian political parties (1885-90). It was not widespread, however. In fact, it was launched by a few who believed in the importance of self-defense as a means toward national liberation, and its followers were the few with arms-in-hand who were weary of the repression, the persecution, the Turkish and Kurdish assaults, the looting, rape and kidnapping that were rampant in the Ottoman Empire. It took years of struggle to move the masses—who were submerged in darkness and had adapted to their lot—to sensitize them to their own predicament and influence them to see the possibility of changing the status quo.

H: In many of the novels, poems, songs, and literature of the Zartonk period, we find a common emphasis on the theme of youth and the importance of passing on values of freedom and justice to the younger generation. Why was there such a strong emphasis on the youth by writers back then?

R.P.: The Renaissance movement began with the enlightenment campaign in a newly established network of schools, that is, the education of the youth. If the Armenian Zartonk ideology called for a change in the destiny of the nation and for the destitute masses to once again become a nation with goals and aspirations, the young generation had to be prepared to take on the commitment and lead the way. The significance of the power of youth activism can be seen throughout the history of mankind. “Youth are the future”— the statement is old and worn but it is true. An example close to our life in America, known to all, is that of the Mexican American Youth Movement of the 1960s and the changes brought about by the relentless activism of Chicano youth. In the Armenian reality of the early nineteenth century, the imaginary characters that Renaissance writers created and hoped to see materialize in real life were young individuals with a profound consciousness of the plight of the nation and an unwavering commitment to bringing change. And we have seen the burgeoning of these young heroes thrusting forward even when their lives were at stake.

H: You’ve written a great deal about literary responses in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide. What can such literature convey to us about the Genocide that historical facts or oral history cannot?

R.P.: Your question leads to the essence of my work as a genocide scholar whose field of research is artistic literature with the Genocide at its core. For many long years now, I have studied the literature of atrocity—to use Lawrence Langer’s terminology— in order to understand the human dimension of this colossal crime which today is called the Armenian Genocide. My writings expose the last cries of the victims of the great injustice that has still not been redressed. They speak of the survivors’ perceptions of the calamity and how their tragic experience has indelibly impacted their psyches and become a debilitating influence in their lives; how harrowing images of their past experience, triggered by visual, aural, olfactory or other associations, revisit them in their waking hours, and return in their sleep when the unconscious overrides conscious control to push dormant images to the surface.

In my reading and explication of these artistic creations—memoirs, auto-biographical novels and other genres of genocide literature—I have tried to illuminate a dark corner of the horrendous landscape of the Armenian Genocide which will never be completely known, and the boundless sea of personal and collective pain and suffering that will never be fully recognized. Although I provide historical background to the places and events under discussion in my work, I never attempt to prove the veracity of the Genocide. It is there as the point of departure, as the source of the breach in Armenian life and all the paradigms of responses to historical catastrophes, and the source of the new reality which is life in the diaspora.

Literary responses to the collective catastrophe reflect the reality perceived by the writers. These writings are the truth as it happened. The reader relates to that truth and absorbs it like no other document or fact sheet.  Allow me to quote a passage from my most recent book which discusses the same issue and demonstrates the intrinsic value of Genocide fiction and symbolic poetry “as elucidators of universal truths that lie at the roots of historical facts, putting inconceivable realities into human perspective… assisting readers to grasp the meaning of a historical event.”

Allow me to quote a passage from my most recent book which discusses the same issue and demonstrates the intrinsic value of Genocide fiction and symbolic poetry “as elucidators of universal truths that lie at the roots of historical facts, putting inconceivable realities into human perspective… assisting readers to grasp the meaning of a historical event.”

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, a Jewish Holocaust scholar, once declared that “The Holocaust has already engendered more historical research than any single event in Jewish history, but I have no doubt whatsoever that its image is being shaped, not at the historian’s avail, but in the novelist’s crucible.” Indeed, it is the artist’s creative power that can capture the unthinkable horrors of genocide and bring them within the scope of the reader’s imagination. That is the power of the pen.

H: Over recent years, there has been a small but growing number of Turks who have begun questioning the denialist narrative of Turkey regarding the Genocide. A significant proportion of these individuals have been writers, poets, novelists, and literary figures such as Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak. What role do you feel literature is playing in the development of a critical voice in Turkey on the Genocide?

R.P.: There is certainly an ongoing metamorphosis at the intellectual level in Turkey, a change in perceptions of the Turkish past, to the extent of questioning the official Turkish narrative. And this is not so much a matter of confronting the denial of the Armenian Genocide, but of challenging the Republican narrative based on the idealization of the founders of the Republic— many of whom were important political figures during the late Ottoman period and, thus, perpetrators of the Armenian massacres—and of questioning the denial of the multiethnic, multireligious and multilingual makeup of Turkey. These intellectuals are in quest of their own true identity. They are struggling for the democratization of the republic and for the lifting of censorship on intellectual endeavors. Their influence on public opinion outside Istanbul is minimal, I would say, but change is in the making. It is undeniable. And the effect of artistic literature such as Orhan Pamuk’s Snow, Elif Shafak’s The Bastard of Istanbul, Fethiye Çetin’s My Grandmother, Kemal Yalçın’s You Rejoice my Heart, Mehmet Uzun’s Pomegranate Flowers, and other works are gradually being felt. Of course, it is also undeniable that these artistic creations or memoirs are supported and reinforced by historical findings, by the books, exposés and discourses of historians, scholars and human rights activists such as Taner Akçam, Ayse Gül Altınay, Fatma Müge Göçek, Osman Köker, Hülya Adak, Ayse Günaysu and others.

H: What are your thoughts on the rapid spread of modern technologies and the popular phenomena of social media today? Can these platforms serve as useful tools for a modern, 21st century Zartonk and revival of Armenian literature?

R.P.: The spread of modern technology and the popularity of social media can be useful and harmful at the same time. The positive impact of this medium, so familiar to the young generation, is undeniable if used with a controlled effort, such as initiating monitored discussions, disseminating ideas, promoting understanding and support for the Armenian Cause and literature. It is possible today to send out information, organize fan clubs and groups, or rally support for or against an Armenian related piece of news in a matter of hours through Facebook and the like.

However, the downside of social media is that it does not lend itself to serious literature and is mostly a space for quick notes, observations, and so on. As for casual online discussions, they can go out of control and boil down to useless chat. A revival in literature in Armenian? I doubt this. A unified easily accessible medium in cyberspace in Armenian is yet to be developed.

H: Do you have any upcoming projects or research you can tell our readers about?

R.P.: Yes, of course, and thank you for this question. My third book on Armenian Genocide literature was published in March this year, and I am already working on the next volume to complete my interpretation of the perceptions of the Genocide by Diasporan Armenian survivor writers of the first, second and third generations.

Meanwhile, I have been working on the project of teaching the Armenian Genocide to Armenian students in K-12, initiated years ago by the Board of Regents of Prelacy Armenian Schools. I have perfected the project, adding missing materials and lesson plans for each age group, and I introduced it at the biennial educational conference sponsored by the Ministry of Sciences and Education of the Republic of Armenia. Because of the enthusiastic reception of the project by Armenian teachers from all over the world, the Ministry of Education agreed to adopt the project, prepare an online version of it and offer it for use by all interested parties, free of charge. It is now posted on the Ministry’s website, at www.spyurq.dasagirq.am, to be exact.

In participating in the 2012 conference this summer, my goal will be to publicize the project and work for its worldwide distribution and dissemination so that every Armenian student, wherever he or she may be, will have the chance to learn about this important turning point in the history of the Armenian people, through age-appropriate materials, tools and methodologies.

I want to see Armenian youth armed with the knowledge of history and of Armenian national rights, logically, without emotional impulse. I want to see Armenian youth properly educated to become committed soldiers of Armenian national aspirations.

Occupy: Teghut, Mashtots Park & Beyond

By: Razmig Sarkissian

Local, diasporan, and even non-Armenian environmental activists have been hard at work in Armenia these past two months. Harnessing the organizing powers of social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube, these activists are mobilizing people – especially the youth – to protest, demonstrate and occupy Teghut, the site of a controversial open-pit mining project in Northern Armenia, and Yerevan’s Mashtots Park, where the construction of a fashion boutique threatens one of the few remaining green areas in the city.

“OCCUPY TEGHUT” and “Դէպի Թեղուտ” graffiti tags have sprung up all around the city of Yerevan, along with videos on YouTube of activists tagging buildings. A Facebook group called “Save Teghut” has garnered thousands of members who post pictures, videos, news articles, and express their frustrations with the current state of Armenia’s long neglected environment. Activists are capitalizing on this frustration and turning it into action, aided by the ability to quickly and efficiently mobilize demonstrators through the internet.

On January 15, the culminated into a march from Yerevan to Teghut, led by over 200 activists , carrying banners reading “We are Teghut” to protest the Armenian Copper Program’s (ACP) plan to turn thousands of acres of lush green forests into an open-pit mining operation. Teghut is estimated to have 1.6 million tons of copper and 100,000 tons of molybdenum underground.

The majority of the protesters, many of whom were in their 20’s, carried digital cameras and smartphones to document the deforestation already taking place. It is estimated one fifth of the forest has already been deforested by the ACP in preparation for the open-pit mine. The protesters were joined by countless local and state media outlets who are just now realizing the gravity of the situation. Police stopped them from marching any further into the mining project.

Environmentalists argue the project will cause damage to the diverse ecosystem, destruction of over 128,000 trees, and the dumping of millions of tons of toxic chemicals and waste into nearby regions, rivers, and water sources. They demand an immediate stop to all mining activities, and propose turning Teghut into a tourist attraction that makes use of the natural beauty of the region rather than destroying it.

Environmentalists argue the project will cause damage to the diverse ecosystem, destruction of over 128,000 trees, and the dumping of millions of tons of toxic chemicals and waste into nearby regions, rivers, and water sources. They demand an immediate stop to all mining activities, and propose turning Teghut into a tourist attraction that makes use of the natural beauty of the region rather than destroying it.

Teghut, located in the Armenia’s northern region of Lori, is one of the only remaining forests in the country with a diverse ecosystem made up of hundreds of exotic animal and plant species, many of which are internationally considered endangered.

In 2008 Armenia’s government granted the Armenian Copper Program (ACP) mining rights to 357 hectares (almost 900 acres) of the forest for 25 years, which activists in Armenia and the international community claim this decision violates countless local and international laws. Adding to charges of corruption, Armenia’s government allowed the ACP to perform its own environmental assessment report rather than requiring a review from an impartial third part group. Their findings were, unsurprisingly, that no harm would come to the region as a result of the open-pit mining.

A bike tour organized last summer by the protesters attracted the support of Armenian rock star Serj Tankian who wrote in a statement, “The destruction of wildlife and environmental havens can no longer be excused for the sake of progress or the attainment of natural resources. Mining is against our combined interest as a people and nation.”

That same summer, a petition addressed to Armenia’s President, Prime Minister, and Parliament collected signatures of over 5,000 citizens, including those of First Lady Rita Sarkisian and former First Lady Bella Kocharian.

Now, the environmentalist spirit is resonating overseas close to home. The ARF “Shant” Student Association is spearheading a “Save Teghut” T-shirt campaign, of which all proceeds will go towards helping the activists. In early February a panel discussion titled , “Armenia’s Environmental Challenges in the 21st Century” was organized in Pasadena by the Armenia Tree Project and Armenian Engineers & Scientists of America in association with AGBU Young in order to foster dialogue about Teghut and the larger scope of environmental problems facing Armenia.

All this momentum is spilling over into the latest set of demonstrations taking place at Yerevan’s Mashtots Park, where activists are protesting the construction of expensive high-end fashion boutiques in one of the few remaining green areas in Yerevan. The activists, the very same who are protesting the developments in Teghut, claim that the construction is illegal as it is in the middle of a public park, and should be stopped immediately.

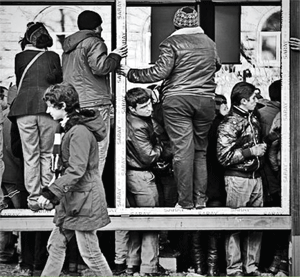

In the past two weeks hundreds have flocked to Mashtots Park, filling in and around the steel frame structure where the boutique is meant to be built. Many have roped themselves together, and some even lied down in front  of cement trucks in an effort to prevent any more construction from taking place.

of cement trucks in an effort to prevent any more construction from taking place.

The construction crew tried to get around the protesters by waiting until the middle of the night to resume welding and hammering. In response, protesters are now occupying Mashtots Park day and night. Protesters also picketed Yerevan’s city hall chanting, “Parks without boutiques,” and “Taron [Yerevan’s mayor] come down”.

However, no official representative from the city has yet to step forward. The city and police claim these boutiques are merely temporary structures which will be eventually removed, which runs contrary to the obvious fact that the boutiques are being built with lasting materials such as concrete, bricks, and steel.

The activists are using the “Save Teghut” Facebook group to organize people and spread information. Their latest event page calls on people near Yerevan to bring tea, blankets, and warm food to support the protesters who are occupying Mashtots Park in the cruel cold of Yerevan nights.

In a surprising turn of events, President Serj Sarkisian personally visited the park in early May. He announced that Yerevan’s Mayor had been instructed to grant the demands of the activists and dismantle the boutiques. By May 10, all of the boutiques were torn down. This marks yet another victory for Armenia’s green movement. Still, nobody knows where exactly this growing movement is headed. What will become of the mining operation in Teghut in light of the victory in Mashtots Park has yet to be determined.

Nobody knows where exactly this growing movement is headed. What will become of the mining operation in Teghut or the boutique construction in Mashtots park has yet to be determined. What is clear however, is that people are finally fed up. Fed up with the government’s backdoor-dealing, oligarch-favoring, corrupt- to-the-core methods of advancing its own interests at the expense and total disregard of its people, its environment, and its nation’s future. People are finally refusing the status quo, finally silencing the cynics indifferent to injustice, finally realizing the power in unity, and finally writing what are only the opening chapters of a movement tenacious in its demand for change in Armenia.

Khoseenk Hayeren, Or You Can Say it in English

William Bairamian

It’s hard learning Armenian. The obviousness of that statement is clear to anyone who knows the language. For students and speakers of the language alike, it’s indisputable. The ancient, convoluted pronunciation rules; the syntactical flexibility that allows you to say the same thing with five words 20 different ways and still get your point across; the myriad dialects suggestive of a much larger land than currently exists – which serves to remind of the vast lands Armenians once inhabited before successive onslaughts and submissions.

But I mean something different. The personal difficulty one might have with those pronunciations, the challenges they may face with constructing the sentences with the fluidity required of a native speaker, or much less, are that person’s business and matters of their mettle. I’m talking about the challenges these individuals who are far from fluent, or even close, that are imposed on them not by language but by people – Armenians.

The most formal Armenian education I got was whatever is gotten by 4th grade. Thereafter, I was all smiles as I entered the public school system – a vicious place unlike the uniform (indeed, pun intended), disciplined, no-nonsense world of Armenian private school. If ever one is interested in testing the tenacity of their teachings with a child, they should send them to public school.

Within a few years – two or three – I was about as assimilated as a sugar cube in water; you could hardly tell me apart. This was not a sudden, unfounded change. I was surrounded by non-Armenians whose attitude toward foreigners, or what they considered foreign, was far from welcoming. Being the friendless new kid in public school, I desperately wanted to fit in. I shirked every aspect of my Armenianness that I could, and language was at the top of what was going on the chopping block.

If ever my parents spoke Armenian with me in public, I would turn red with embarrassment. Their carelessness,- in my slavish, juvenile mind – let the non-Armenians in on the secret that we were not the American I saw myself as. I couldn’t understand why they had immigrated here from Armenian-speaking lands to this place they extolled as what saved them yet they continued speaking Armenian, eating Armenian, acting Armenian. I resolved that American was what I was and that was it.

I played baseball (possibly the most nonsensical of all sports to an Armenian), football (a close second to baseball), I only spoke English, I listened to rock and roll and heavy metal (the latter being the nonsensical parallel of baseball in the musical world, if it could be considered music), I developed a love affair with American muscle cars, and I preferred burger joints and hot dogs to any food prepared at home. I refused to speak Armenian (while my Mom would refuse to speak in English) and, coincidentally, I forgot it, all of it – how to read, how to write, almost completely how to speak.

Success!

Then I met them. Those who I can only describe as racists. Or maybe xenophobes, if we want to be slightly euphemistic. Over the years, they came out of the woodwork in the most unexpected places, in the most subtle of ways. For these people, it didn’t matter how much I tried, how American I thought I’d become – I was still an immigrant, an outsider, a foreigner. And I began to wonder: I was actively attempting to expunge, in earnest, a 5,000 year old culture which I was born into while some non-Armenians around me were clamoring for an identity, whether real or made up. My idiocy slapped me silly.

But I had walked far enough away from the tribe, and for enough time, that I could at least know how to fashion myself. Spiraling into an outwardly extreme supposed Armenian persona was uninteresting to me and, frankly, overdone. I saw “aga, shakhs, aper, khob”, the blotte or tavluh, the crosses or clothes, as replacements for what we had lost somewhere along the way. My familial upbringing, as much as I tried rejecting the Armenian underpinnings, had left its residue. With it came the contrast of what we were against what we thought we were supposed to be. So, I embarked on the excruciating journey of learning how to be Armenian in the truest form I could conceive.

Excruciating. That’s a rough description of what should be a pleasant adventure of discovering the wondrous essence of your being. Or: this is supposed to be fun, not painful. But it is. It is painful when you are trying to eke out words in Armenian, torturing yourself so foreign verbiage doesn’t invade your speech lest you become complicit in perverting the language you are struggling to maintain, and, alas, your fellow interlocutor is more concerned with highlighting your inadequate fluency and, naturally, their superior usage ability – their impeccable reprimands infused with “ishteh” and “yani” – than with acting as a guide toward the realization of, ostensibly, both your goal. The concluding recommendation being, “you can say it in English” or, if especially audacious, switching languages on you without notice, thus surreptitiously opining about the (inferior) quality of your spoken work.

This proclamation from the same person who is likely a steadfast source of the righteous imposition that “bedk’eh khose(e)nk Hayeren” (“we must speak Armenian”)! Imagine the state of your brain as it is trying to compute someone telling you that you must speak Armenian while telling you that if you can’t manage – and it’s obvious you can’t – just switch to the other language that they, since they’re more multilingual than you, can understand just as well. Instances like these may very well be the beginnings of bipolarity.

I’m loathe to offer this as a crusade of solely personal proportion. This is one example of what I know is commonplace. As a Diasporan, and one who not only lives, but works, within its (otherwise supremely pleasant) confines, I am uncomfortably privy to the growing apathy and, in my estimation, lethargy, which has started to overtake the community. It requires much less energy to let your surroundings have their way with your psyche and person than to confront them with the conviction of who you are. It requires an exceptional level of diligence and discipline. And, for those who have taken the valiant plunge into cultural preservation and growth, the last thing on their long list of worries should be the overt or subtle discouragement of those who need to otherwise be the cheerleaders.

I already disdain that I may not ever be able to speak Armenian as beautifully as my parents, or the poets whose gifts I want to read – and understand. But that I not become the charlatan who discourages the believer that they may realize such an unattainable treasure is of similarly paramount importance. To damage the wish of a striver to reach that end is unforgivable.

Hence my gratitude is conveyed to the corps of individuals whose object is not to outdo but to include. Thanks are due that they believe that one’s elevation requires them to elevate, not smile down from upon their perch. Without the sagacity and measured patience of this limited group, the treacherousness of this journey would be compounded unimaginably.

To the the bipolar self-styled linguists, I am writing this in English because I can’t write it in Armenian – I probably couldn’t even say it the way that I wanted without taking twice as long. But, I’ll get there, determined to gain total facility in this unique language, my language. Or, for their understanding ease: yani, no problem, brat.

Hayeren will prosper and perpetuate under the tutelage of the previously incapable upon their mastery of this language they love. Fortunately, history is not made by the faithless.

This piece is dedicated to the haters and the innocent bystanders

What Does It Take To Build A Nation

By: Sanan Shirinian

There are several important elements necessary in the continuous process of state development. Among these are fair and transparent elections, an active and engaged civil society and a functioning judicial system. Today, Armenia seems to be at a turning point and its subsequent steps will be critical for her to develop into a stable democratic nation. Any meaningful attempt to challenge inequity or injustice will require a meaningful alternative to the status quo. These alternatives can be represented through another important element in state development: public policy.

The Hrayr Maroukhian Foundation (HMF) was created in the Republic of Armenia in 2009 by the Supreme Council of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation-Dashnaktsutyun. HMF is a social democratic think-tank that produces academic research papers, linking them to political decision-making and policy. The foundation is committed to the development and advancement of public policy issues and works to strengthen democratic institutions through social and economic policy research.

To date, HMF has produced three policy papers, recommending improvements to the healthcare, housing and employment sectors of Armenia. Through a designated working group of experts focusing on each specific policy area, these studies aim to implement the populations’ right to quality housing, employment and accessible and affordable health care.

Currently, new working groups are undertaking three other sectors in need of reforms: agriculture, mining and education. They will be examining the current state of these areas and recommending alternative, original and applicable solutions from a social democratic perspective. Working at HMF, I am privileged to be taking a part in the cultivation of our nation on a daily basis, and am proud of the work we produce. There is a difference when conservative parties in Armenia preach socially favorable rhetoric and when true leftist parties create policies in the interest of the public. The policies produced by this foundation reflect social democratic principles and therefore work to defend the general welfare of the population.

Currently, new working groups are undertaking three other sectors in need of reforms: agriculture, mining and education. They will be examining the current state of these areas and recommending alternative, original and applicable solutions from a social democratic perspective. Working at HMF, I am privileged to be taking a part in the cultivation of our nation on a daily basis, and am proud of the work we produce. There is a difference when conservative parties in Armenia preach socially favorable rhetoric and when true leftist parties create policies in the interest of the public. The policies produced by this foundation reflect social democratic principles and therefore work to defend the general welfare of the population.

However, during my fifteen minute walk to work every morning, I think about the endless problems of our nation, from population decline and extreme poverty, to hostile neighbors and exploitive leaders. I cannot help but ask myself, “Is what we’re doing enough?”

Policy interventions are done in a complex system where many other factors must be considered. They are surely an important part of the entire process of nation-building, but their potential is compromised when entrusted to the hands of corrupt officials. In a hierarchical environment, such as the one in Armenia, there is bound to be resistance to progress and difficulty rallying the public to enforce necessary change. Therefore, along with policy analysis there needs to be political will and public pressure to implement solutions.

There also needs to be a collective effort of society, participating in different ways. HMF is working to implement change through policy alternatives, but we need more to do the same. We need more people joining the environmentalists protesting in the streets day and night. We need more scholars receiving their doctorate in political science and international development. We need more women raising their voices in the name of equality. In order to reach the level of stability and even prosperity our nation deserves, we need this intricate network of participants working alongside each other.

To say that the current government of Armenia is solely dedicated to the special interests of the elite is no major revelation. It is fairly obvious that the personal gain of the privileged upper class and the preservation of  business interests is reinforced at the expense of the nation’s prosperity. This is a direct infringement on people’s freedoms. We have failed to even create a façade of formal institutions to give the illusion of democracy. And the question on everyone’s mind is the same: How do we fix it?

business interests is reinforced at the expense of the nation’s prosperity. This is a direct infringement on people’s freedoms. We have failed to even create a façade of formal institutions to give the illusion of democracy. And the question on everyone’s mind is the same: How do we fix it?

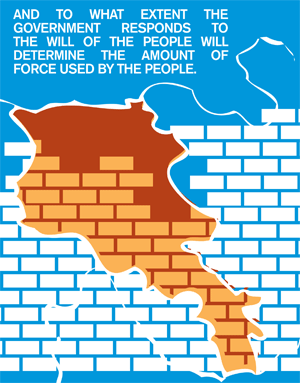

Some may think that Armenian society should push for idealist notions of revolutionary uprisings. Others believe we need to work towards democratic manifestations of social and political progress. I suppose the former sees genuine victory being born from an abrupt spark that will ignite a revolution and uproot our entire system of operation. Conversely, the latter trusts a process of gradual democratic accomplishments. All I can be sure of is this: whether a transformation comes from uprisings like we have seen across the Middle East or through more steady means, it can only come from the force and the will of the people. That is the only clearly definable victory. A government established on the basis of the general will is a victory. And to what extent the government responds to the will of the people will determine the amount of force used by the people.

Therefore, whether you are working at a policy institute, campaigning for the elections or organizing a rebellion, stay active. Your participation is a necessity in establishing a politically stable, socially just and economically prosperous nation.

Summer 2012

By Any Means Necessary: AYF Seminar Explores Liberation Movements Past and Present

by Razmig Sarkissian

“We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary,” said Malcolm X in 1965, the year he was assassinated.

“By Any Means Necessary,” a phrase first used by French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre and later popularized by Malcolm X, was the theme of the Armenian Youth Federation’s (AYF) 2012 Educational Seminar which took place over the June 1-3 weekend, educating participants about freedom fighters from the past and present.

The seminar, which hosted a number of members from the AYF, local Armenian Students’ Associations and other young Armenians, sought to foster a spirit of social awareness by examining the liberation movements of different peoples including, but certainly not limited to, Armenians.

“It is imperative for young Armenians to have opportunities to discuss historical liberation movements,” said Tamar Baboujian, Executive Director of AYF Camp and former AYF member, who was also a discussant at the seminar. “It broadens their perspective and evokes compassion for people internationally.”

Jumpstarting the weekend’s lecture series with a video presentation and discussion about Guerilla movements was Baboujian, along with Razmig Sarkissian and Berj Parseghian, who is pursuing a Masters in Education and has a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The presentation used multimedia from manifestos written by the likes of Che Guevara and Mao Tse-Tung, to video clips of the films “Malcolm X” (1992), “The Motorcycle Diaries” (2004) and “The Weather Underground” (2002), covering a breadth of issues from effective guerilla tactics, the American Civil Rights movement, Latin American liberation struggles, and anti-Vietnam activists.

The presentation used multimedia from manifestos written by the likes of Che Guevara and Mao Tse-Tung, to video clips of the films “Malcolm X” (1992), “The Motorcycle Diaries” (2004) and “The Weather Underground” (2002), covering a breadth of issues from effective guerilla tactics, the American Civil Rights movement, Latin American liberation struggles, and anti-Vietnam activists.

Each clip was followed by insightful commentary from participants and vibrant discussions about core issues underpinning these movements such as the costs and benefits of non-violent vs. violent approaches to a cause.

The following day, Jovian Radheshwar, a lecturer in Political Theory at California State University Channel Islands and PhD candidate at UCSB, gave a lecture about cultural and ideological awareness, the effects of imperialism and globalization, and the India-Pakistan divide.

Among the many themes Radheshwar’s lecture covered were “revolutionary solidarity” and “radical awareness of reality.”

To explain the concept of “revolutionary solidarity,” Radheshwar used the example of local shopkeepers during the riots in Britain a few years ago. The riots were led by members of the working class, but did not have wide-spread support among all in the working class. Many local shopkeepers called on the police to stop the riots, even though the cause included them as well, so that they could resume their day-to-day business. Revolutionary solidarity would have entailed the shopkeepers supporting the cause despite the short-term business loss due to the riots.

Revolutionary solidarity, thus, is realizing that outside one’s individual community are others in similarly oppressed conditions, and breaking down boundaries to identify with their cause as well, because at the end of the day their cause is your cause.

This ties into the concept of being “radically aware of one’s reality” in the sense that you need to be aware and almost hyper-conscious of happenings in the realm of politics, society, culture, philosophy and anything else, and be a contemporary of the world. Otherwise you lack the tools and knowledge necessary to be a true socialist or revolutionary.

Leading the next lecture was Allen Yekikian, Chief Technology Officer at Operation HOPE with a background in Armenian history, who discussed Armenian liberation in the 19th century, and the impact the “Zartonk” movement had in shaping Armenian identity and future generations of freedom fighters.

“Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter are today what the printing press and newspapers were in the 19th century for the group of intellectual Armenians who manufactured and disseminated the “Zartonk” cultural awakening to the oppressed and impoverished Armenian masses,” said Yekikian.

His take-home message was that an entire cultural renaissance was born with technology we consider crude today, and that the opportunity is ripe to create an “iZartonk” with the unimaginable technology, means, and capabilities offered in today’s digital environment.

Wrapping up the weekend’s lecture-series was Nora Injeyan, who is pursuing a Masters in History with an emphasis on modern Armenian history from the University of California, Irvine.

She explained the conditions which led to the fall of the Soviet Union and gave birth to Armenia’s second independence, such as democratization of the political system, and the liberalization of cultural expression all ushered in by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader. Injeyan then turned the focus to the current problems facing Armenia today.

She explained the conditions which led to the fall of the Soviet Union and gave birth to Armenia’s second independence, such as democratization of the political system, and the liberalization of cultural expression all ushered in by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader. Injeyan then turned the focus to the current problems facing Armenia today.

Participants collaboratively identified some of those challenges as widespread electoral corruption, poor economy, and an emigrating population. This led to a vibrant discussion of the causes of those problems, and a lengthy brainstorm about the ways in which Diasporan activism can aid this still-infant nation.

“It was very reinvigorating to interact with AYF members discussing broader issues of liberation and how to draw lessons from other struggles relevant to our community today,” said Myrna Douzjian, Director for the weekend’s seminar and a former AYF member, who is pursuing a PhD in Comparative Literature in Russian and Armenian from the University of California, Los Angeles. “Participants delved into the core of what it means to be an Armenian activist today, all while exploring and analyzing other national movements,” Douzjian added.

Freedom fighters challenge mankind’s history of conflict, oppression and injustice by fighting for the empowerment and liberation of the oppressed. This fight is sometimes physical but more often a metaphysical one, aimed at overturning dominant societal conceptions and norms. In order to bring into existence a world devoid of violence where the rights of all human beings are tolerated, our generation must arm itself with the knowledge of past and present struggles against oppression, be emboldened by the determination of past freedom fighters, and practice revolutionary solidarity to fight injustices anywhere they may occur against any group of people, by any means necessary.