I Was Told There’d Be It ?

By: Ani Sarkisian

The way I remember it, the first time I went to Karahunj there wasn’t even a road. It was my very first time in Armenia, everything was brand new, and the constant overload of sensory experience for three months renders my memory suspect when it tells me that we veered off the main highway into a field and all we had to guide us was our driver’s infallible sense of direction (and really, when it’s your first time in Armenia and you’re the only kid who doesn’t speak the language, you want to find the guy with the infallible sense of direction). I was tagging along with a couple of friends on their AYF excursion, knew nothing about Armenia, and I think when I heard someone mention “Stonehenge,” I rolled my eyes.

By now, you may have heard of Karahunj (or Zorats Karer). After being featured in a History Channel documentary as well as a segment on CNN (videos that were subsequently shared on many an Armenian Facebook wall), you may recognize it asArmenian Stonehenge. The more than 200 stones in the layout have been standing sentinels at the edge of Sisian in the Syunik province for around 7500 years, making it 4500 years older than Stonehenge in the UK. Some of the stones weigh more than 50 tons, and 85 of them have man-made holes that form calculated angles when connected, drawing the eye to certain points in the sky.

International teams of archeologists, astronomers, and historians have competing theories to account for what it could exactly signify. It could be the world’s oldest observatory and calendar. Another theory, taking changes in the tilt of the Earth’s axis into account, is that the stones appear to line up with the constellation Cygnus (a swan or a vulture, depending on where you’re from), which symbolized an entry into the stars above; the idea is that our ancestors were possibly trying to tell us where we came from. There’s also the ominous thought that our ancestors were trying to leave a message, warning us of cataclysmic dangers that can be read in the stars. There’s even a theory that the first inhabitants of Great Britain were Armenians, meaning they brought their knowledge of astronomy and the concept of a Stonehenge and the tradition of khachkars to Europe. Supporting this theory is the fact that “kar” means stone in Armenian, and “hunge” translates to something like “bunch,” but the word “henge” has no origins in the English language, making its existence in the name Stonehenge all but arbitrary without the Armenian link.

Of course, I had no idea about any of this on my first trip to Karahunj. Our motley crew also included my host sister and a hitchhiking soldier on his way home, and we were all too worn out and too busy chattering to each other to ask too many questions about what we were about to see. I remember staggering out into the approaching twilight and fog, unsure of what I was looking for. “Stonehenge,” I thought to myself, and started searching for rocks in the shape of a pi sign. My eyes identified a seemingly random collection of rocks that slowly revealed a pattern, snaking into the distance and towards a central point. I remember the first stone I saw with a hole and feeling my heart thud.

In the distance, one of the stones broke itself in half and walked towards us; it took me a minute to realize it was a man who had been sitting out there all alone and reading a book. He approached our group and greeted us. My host sister, Rosa, whispered a translation and it turned out the young man was from Yerevan and was studying archeology. Because there were no signs or guides to explain the stones and their mysteries, he spent his summers sitting there waiting. “For what?” I asked. Rosa relayed my question, and the young man’s eyes lit up. He answered, Rosa smiled, and she grinned and turned to me. “For you, of course!” He proceeded to walk us through and explain the theories, placing his hands on the stones with respect and affection. He spent he summers out there in hopes that someone, or some group, would make the trip so that he could share his knowledge and revel in the enigmas of Karahunj.

Nowadays, UNESCO signs and a tourism kiosk give visitors a basic idea of what they’re seeing. But when I think of Karahunj, I always think of that solitary man in a nondescript field surrounded by the wisdom of our ancestors, patiently waiting for someone to join him: to stare at our past in wonder, to share the secrets of the ancients, to speculate, and to remember that life is mostly a mystery.

Artsakh: The Cradle of Liberation

Jtrdooz (Shushi Gorge), Artsakh: The story is that in May of ’92, over three nights (sleeping in caves during the day) something like 30 Armenian soldiers scaled the cliff to liberate Shushi. In the meantime, other forces came in from multiple directions. The result was that the Azeri forces thought they were surrounded by much larger forces than they actually were, and they retreated. The view from the cliff is extraordinary, and there’s a waterfall. Everyone loves waterfalls.

Ganzasar Monetary, Artsakh: The legend is that the priest in Gansasar held off the Azeri forces with two other priests for hours using the shotguns they keep under their vestments. We don’t know if that’s true, but when Ani went there for the first time, she felt the energy of the head priest before she saw him. To this day she main tains she felt some sort of force pass by her, and when she turned to look he was walking away, robes flapping in the wind, radiating some sort of awesome (in the true sense of the word. not as in, “nachos! awesome!”). Gansasar takes an hour or so to get to from Stepanakert, but the ride is incredible and the setting is breath-taking. Keep a lookout for the mortar embedded in the side of the outer walls. And don’t anger the priest; Lord knows what he’s capable of.

tains she felt some sort of force pass by her, and when she turned to look he was walking away, robes flapping in the wind, radiating some sort of awesome (in the true sense of the word. not as in, “nachos! awesome!”). Gansasar takes an hour or so to get to from Stepanakert, but the ride is incredible and the setting is breath-taking. Keep a lookout for the mortar embedded in the side of the outer walls. And don’t anger the priest; Lord knows what he’s capable of.

The Shkhtorashen Tree: The 2000 year-old tree: by now, this tree must hate us. Beautiful, majestic, breathtaking, and “big enough to hold a party inside.” (snap goes the camera) “Guys! Guys it says here this tree is big enough to have a party inside!” (snap) “Can you imagine having a party in a tree? Ha ha!” (snap snap) “Ohmigod guys you totally COULD have a party in here, will you take my picture with the tree?” (snap) This tree has probably MET Ghenkis Khan (who knows, maybe he said to his friend “Dude, sketch me in front of this tree!”) and all people can talk about is whether or not they could fit a turntable in there. But guys, seriously, it’s massive, and you could totally have a tea party inside if everyone stands up so they don’t get muddy. Snap.

Can Armenia’s Economy Thrive on Services

There is no shortage of recent success stories about national economies skipping the development of a large manufacturing sector and instead building a prosperous economy on a robust services industry alone. Countries like Ireland, Norway, and India have largely forgone manufacturing and instead focused their economies on services, the sector of the economy that includes things like finance, software development, design, IT, media, customer support, and other services that are increasingly becoming easier to trade in thanks to technology.

The traditional view of an economy’s services sector is a negative one; it is frequently accused of being unproductive and not valuable to an economy’s international competitiveness. This may have been true in the recent past; services have traditionally been immobile and involved only in the domestic economy, contributing little to a country’s exports. However, with the emergence of better communications technology the traditional barriers to exporting services have waned. India and Ireland have been able to capitalize on this opportunity and have built successful export economies based largely on services, attracting massive foreign investment and trade.

The traditional meat and potatoes of an economy has always been thought to be the manufacturing sector. Development economists still preach the tried-and-true methods of moving labor from agriculture to high-productivity manufacturing jobs. This is, undoubtedly, how economies have developed in the past; see South Korea, Taiwan or China as recent examples.

But the outlook on manufacturing is not as rosy for Armenia. Sure, Armenia was a manufacturing powerhouse in the Soviet Union, but without the protection of the centrally planned economy, Armenia is in a whole new ball game. In the new economic climate that Armenia finds itself in – with no sea ports of its own, eastern and western blockades, and an underdeveloped infrastructure – the manufacturing industry faces many obstacles. Meanwhile, a potentially strong services sector has many opportunities to look toward, providing new hope, at least for the near future.

Since independence, Armenia’s services sector has overtaken its manufacturing. And in the 2000’s, the services sector has been the clear driving force behind Armenia’s high economic growth rates. As a portion of GDP, Armenia’s services sector holds 46 percent, while it employs 36 percent of the labor force. One needs only to cruise down an avenue in Yerevan (driving carefully of course) to see evidence of this: advertisements for VivaCell-MTS, Ameriabank, and other such service corporations litter the city.

There are a number of reasons why a services-oriented economy offers better prospects for Armenia. For one, services – which are largely based on telecommunications and which lack the need for physical transportation of goods – can bypass Armenia’s troubles with infrastructure and its lack of sufficiently accessible trade and transportation routes.

A services industry also circumvents the need for a low-wage, exploitable labor force that is necessary in most newly industrializing economies. Armenia does not possess, nor should it want such a labor force. Services jobs provide far better working conditions. The services industry is also a boon when it comes to opportunities for women. Services jobs are equally accessible, if not more accessible, to women as they are to men. Increased opportunities for women means not only greater social equality, but also increased incomes for households.

Lastly, services have far less impact on the environment. This is a very attractive offer to Armenia, which suffers its fair share of environmental degradation and problems arising from it.

Service-based is the industry that the global economy is shifting towards, with more room to grow than other industries and a plethora of new opportunities that well-prepared countries can seize. Considering that most of Armenia’s current manufacturing sector consists of raw commodities exports and not much high-value production, equipping itself to reap the benefits of favorable services opportunities is the most sensible thing Armenia can do.

If Armenia were to embrace services it would have no lack of useful resources. Armenia has an enthusiastic diaspora, who are educated and possess skills and knowledge about the services industry that they can introduce to Armenia, not to mention the capital with which to start such business ventures. Armenia also has a capable workforce for the services, with decent education, good technical knowledge, and plenty of artistic skills. The only thing missing from the Armenian labor force is an English-speaking workforce, a vital component to any service economy.

Of course, it might be grossly overoptimistic to hope that Armenia, with its scores of growth-inhibiting problems such as corruption and an oligopolistic economy, is actually prepared to take on this challenge. But there are a number of things the Armenian government can do to create a more competitive services sector. The most important task would be to invest more in education, especially in technical skills. An ideal decision also would be to replace Russian language learning courses in school with English.

The Armenian government should also invest in services infrastructure, further improving and upgrading telecommunications lines for example, encouraging more widespread Internet access and establishing helpful regulatory and oversight agencies.

Many of these needed investments into education and infrastructure have been undertaken by the private sector as business investments, as in the case of the massive telecom infrastructure overhaul that has been carried out recently almost exclusively by private companies. But the Armenian government should not rely on the benevolence of the private sector or non-governmental organizations; it should resolve to carry out these tasks on its own if it expects to guarantee its goals.

The most important thing that the Armenian government needs to do, however, is to overcome its crippling system of oligopolies and to encourage vigorous competition. To stay competitive internationally, the government must allow the services market to operate freely, intervening not to provide favors for government-connected pals, but to encourage more competitiveness and to protect nascent enterprises. On the same token, the government must allow the services industry to compete with foreign firms and do business with them; only in this way can Armenia bolster the quality of its services exports. With help from government, an Armenian architecture firm or web development company has the potential to be as large a company as some of its best-known European counterparts.

The recent opening of the Tumo Center for Creative Technologies in Yerevan provides hands on education in to youth in a state-of-the-art facility. This type of instruction in the fields of animation, gaming, web development and video will lead to a broadening of career opportunities for our new generation. The AYF, with its work in the Youth Corps program and through its donations of computers and books, among other efforts, can help towards this goal as well, supplementing the work needed to prepare for the future of Armenia’s services industry.

Ughtasar: The Petroglyphs of Armenia

By: Maro Siranosian

The petroglyphs, or rock engravings, of Ughtasar can be found all over Yerevan; they are inscribed onto silver jewelry, painted onto coffee cups, traced into hand-made pottery, and they adorn the walls of cafes. Reaching the actual petroglyphs of Ughtasar (“ught” meaning camel and “sar” meaning mountain, due to the resemblance of its peaks to the humps of a camel) can be a bit of a challenge, and as with most of Armenia’s noteworthy sites this provides half of the trip’s excitement and intrigue.

Located in the Syunik mountain range about 20 miles from Sisian in southern Armenia, the petroglyphs can only be accessed by an uphill climb in a Soviet-era UAZ. UAZ stands for Ulyanovsky Avtomobilny Zavod, or the Ulyanovsk Automobile Plant where the sturdy Russian 4×4 is manufactured. The trek up the mountain is much like riding Disneyland’s beloved Indiana Jones Adventure 200 times without stopping. Your slight, unassuming Armenian driver will be transformed into a superb navigator at the helm, maneuvering through ditches and over large boulders with ease as you bounce around the back of the UAZ desperately trying to absorb some of the pristine scenery without knocking your head against the window too many times. At some point after the first hour of driving you have no choice but to get out of the vehicle and continue on foot, as the road becomes too steep for even the tank-like UAZ to scale it with so many passengers. This is the part of the trip when some members of your party, possibly your father or mother, will start cursing the moment they agreed to come here with you in the first place; this was, after all, supposed to be a vacation.

Located in the Syunik mountain range about 20 miles from Sisian in southern Armenia, the petroglyphs can only be accessed by an uphill climb in a Soviet-era UAZ. UAZ stands for Ulyanovsky Avtomobilny Zavod, or the Ulyanovsk Automobile Plant where the sturdy Russian 4×4 is manufactured. The trek up the mountain is much like riding Disneyland’s beloved Indiana Jones Adventure 200 times without stopping. Your slight, unassuming Armenian driver will be transformed into a superb navigator at the helm, maneuvering through ditches and over large boulders with ease as you bounce around the back of the UAZ desperately trying to absorb some of the pristine scenery without knocking your head against the window too many times. At some point after the first hour of driving you have no choice but to get out of the vehicle and continue on foot, as the road becomes too steep for even the tank-like UAZ to scale it with so many passengers. This is the part of the trip when some members of your party, possibly your father or mother, will start cursing the moment they agreed to come here with you in the first place; this was, after all, supposed to be a vacation.

After you pass the worst of it and can climb back into the car, it’s only a short drive to the lake and the petroglyphs at the top of the mountain. The first glimpse of the small, crystalline glacial lake makes the drive worth it, no matter how much you may have been knocked around: it is glass-like and still, providing a perfect mirror of the sky and the surrounding peaks, and over 2,000 decorated rock fragments extend to the foot of the mountain. If the sun is shining, the rocks glisten with a greenish iridescence. The petroglyphs, some believed to date back to the Paleolithic Era (12,000 BCE), are carved onto dark brownish-black volcanic stones left behind by an extinct volcano. Although the site was discovered in the early 20th century, it was not really studied until the 1920s and again in the late 1960s; it is still not fully understood today.

The carvings on the rock fragments depict hunting scenes, a wide array of animals, spirals, circles and geometric shapes, and even zodiac signs. Research suggests that the area served as a temporary dwelling for nomadic cattle-herding tribes, and studies of the rock carvings indicate that they were in use for hundreds of years, with peoples of later eras adding their ownengravings to the stones. According to the research of Hamlet Martirosyan, the pictograms of Ughtasar represent a writing system called “goat writing”.

The carvings on the rock fragments depict hunting scenes, a wide array of animals, spirals, circles and geometric shapes, and even zodiac signs. Research suggests that the area served as a temporary dwelling for nomadic cattle-herding tribes, and studies of the rock carvings indicate that they were in use for hundreds of years, with peoples of later eras adding their ownengravings to the stones. According to the research of Hamlet Martirosyan, the pictograms of Ughtasar represent a writing system called “goat writing”.

Many scholars believe that this was due to the large number of goats drawn on the stones, but according to Martirosyan it is because in the ancient Armenian language, the words “goat” and “writing” were homonyms (words of differing meaning that sound the same). They would use these homonyms to express concepts through pictures, thus the abstract concept of “writing” (which in ancient Armenian can be expressed with words like “shar” – arrange, “sarel” – compile, “tsir” – a line) found its reflection in the representation of a goat (“zar”), because the words for “writing” and “goat” sounded the same. As English speakers, we can think of it as representing the pronoun “you” with a picture of a ewe (a female sheep). Goats are a prevalent theme on the stones, possibly because the word “dig” in ancient Armenian meant goat and was close enough to “diq,” the ancient word for gods. By combining abstract signs with the images of animals and people in horizontal or vertical rows, prehistoric engravers were able to convey specific messages.

The true beauty of Ughtasar lies in its seemingly untouched nature. You won’t find traces of khorovadz (barbeque) fires next to the lake or trash sprinkled among the rocks; there isn’t a visitor center selling mugs and postcards; there are no tour guides hounding you to listen to the history of the petroglyphs. You are free to roam the mountainside and sit among the prehistoric graphic expressions, pondering what might have caused ancient Armenians to scale the uninviting peaks and leave their mark. At about 10,500 feet above sea level, the air is some of the cleanest you’ll breathe in Armenia outside of a climb to the top of Mount Aragats, Armenia’s highest point. Due to its elevation the climate is always crisp and patches of snow speckle the mountain year-round.

Today, the mountain perch hosts annual spiritual gatherings and retreats. Surrounded by the marks of peoples past, modern visitors partake in the same natural beauty, serenity, and mystery that the lake has provided for thousands of years.

When you finally reach Sisian again after practically tumbling down the mountainside, you feel like you’ve just returned from a trip to the moon or some equally far-flung and unreachable place. You feel as if you’re waking from a dream, a dream whose constant jerking scenery caused you to fall from your bed, hitting your head a few times along the way. You are left with some amazing bruises to help you recall it instantly for days to come.

More To See Outside of Yerevan

Dilijan and Parz Lich: Located in Northern Armenia, Dilijan is like the Armenian Alps. Check out the beautiful old wooden homes in Old Dilijan or take a hike around the crystalline Parz Lich.

Aragatz: Get caught in a lightning storm and be pelted with hail on the peaks of Armenia’s highest mountain. Slide down through the snow and tap dance on flat stones that sound like xylophones. Make sure you have your transportation to get down the mountain worked out before hand or discover yourself with the surliest group of friends you’ve ever had. Also make sure to admire the nomadic Yezidi settlements on the way up the mountain.

Aragatz: Get caught in a lightning storm and be pelted with hail on the peaks of Armenia’s highest mountain. Slide down through the snow and tap dance on flat stones that sound like xylophones. Make sure you have your transportation to get down the mountain worked out before hand or discover yourself with the surliest group of friends you’ve ever had. Also make sure to admire the nomadic Yezidi settlements on the way up the mountain.

The other Shores of Lake Sevan – Noraduz and Shorzha: Buy fish from local fisherman who hold up their hands as an indication of the size of their fish, and not the size of the equipment that caught it. Check out Noraduz Cemetery with its medieval khachkars and head around the lake to Shorzha to feel like you’re the only person in the world.

Karahunj and Ughtasar: You might see people with stethoscopes trying to pick up vibrations in the rocks. If you’re truly adventurous, take a Soviet jeep up a nearby mountain to get to Ughtasar, where you’ll find the mountainside scattered with petroglyphs.

Geghard and Garni: Geghard is a beautiful monastery partly carved out of a mountain. Just nearby, Garni is the site of Armenia’s last standing Pagan temple. Don’t miss the opportunity to visit the local lavash factory and lunch with local gangsters. Just don’t get into their large black SUV, even if they offer you land and livestock. Food for thought.

Goris and Khndzoresk: The last time Ani visited this place, she acted like a sullen teenager and refused to take in the breathtaking views. Don’t do that when you go. Do feel free to crawl into ancient caves where our ancestors used to live. Don’t lean against the car glaring at your parents, even if they started it. Because they did.

Tatev and Devil’s Bridge: The beautiful monastery of Tatev can only be reached by hiring a driver named Tarzan and his orange marshrutka (minibus). Well, no, that’s not really true, but it should be. Tatev can also be reached by the world’s longest teleferic (aerial tramway). Before you head up to the monastery make sure to check out Devil’s Bridge, a natural bridge above the Vorotan river. You can climb down the edge of the bridge to bathe in mineral pools and explore the taverns below with theirimpressive stalagmites and stalactites.

Lastiver: Climb through caves with carvings pre-dating Christianity and chip a front tooth while jumping off a large waterfall. Lastiver is one of our favorite adventure spots. If you like nature and hiking and benches made of tree trunks, this spot is a must. Go ahead and build a fire, City Kid. Builds character.

Lastiver: Climb through caves with carvings pre-dating Christianity and chip a front tooth while jumping off a large waterfall. Lastiver is one of our favorite adventure spots. If you like nature and hiking and benches made of tree trunks, this spot is a must. Go ahead and build a fire, City Kid. Builds character.

Ani (from Armenia): The only site on our list that might frustrate you, the medieval city of Ani can only be seen from Armenia and not actually visited. But if you can’t make it to Turkey to visit Ani properly, the trip to the border is definitely worth it. Ani headed straight to the border, charging through the weeds until they reached her hips, and only turned back when the soldiers at the Turkish base on the other side of the border spilled out in alarm. True story.

Haghpat, Sanahin and Berd: Berd was a once thriving city and served as a hub when the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan was still open. The townspeople now find themselves on the frontline and remember the days when the villages on the other side of the border contained neighbors and friends. They have a unique perspective regarding the Kharabagh conflict, and are remarkably forgiving considering they were nearly bombed to proverbial smithereens. The monasteries at Haghpat and Sanahin were chosen as UNESCO sites, need we say more?

Welcome To Javakhk

Photos by Tamar Baboujian

Young Armenian standing in the fields of Madatapa Lake facing Armenia, illegally raising the Armenian flag.

Armenian children playing soccer at Rupen Der Minassian Armenian School – Akhalkalak, Javakhk.

Classroom being used at Rupen Der Minassian Armenian School

Armenian woman standing at the locked door of church ruins, where locals light candles and place them at the doorstep – Deeleef Village, Javakhk.

Handmade irrigation system bringing water from the mountain to the homes and farms in Deeleef Village, Javakhk.

Armenian farmers with sickles, outskirts of Akhltskha, Javakhk.

Abandoned building in the Rupen Der Minassian Armenian School

Third generation Armenian spice merchant at the local bazaar with incredible basturma – Akhalkalak, Javakhk.

Armenian child who was playing in rubble – Akhalkalak, Javakhk.

Old Armenian woman selling herbs, smiling when she learned the last name of our local friend and found a relative – Akhalkalak, Javakhk.

The ruins of portions of the Fortress of Akhalkalak

Trademark stork nest found throughout Javakhk.

Jerusalem: A Souvenir from the Armenian Quarter

In Memoriam: Vahik Aroustamian, Beloved Uncle (1955-2007)

In Memoriam: Vahik Aroustamian, Beloved Uncle (1955-2007)

By: Gayane Khechoomian

Last summer I woke up on the rooftop of a hostel in the Jewish quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City. Before the sun had a chance to let me know I had been sleeping outside, the Islamic ‘call to prayer’ sounding from the mosque speakers reminded me that even at 5 a.m., God is Great (“Allahu Akbar” in Arabic). Three hours later, the church bells commanded my attention. I was wide-awake, living a dream.

This ancient part of the world, where the four corners of the earth meet, is the site holiest to the three Abrahamic religions. The Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Armenian Quarters make up this 0.35 square mile fortress-like city. Here, the cobblestones of narrow streets are a time machine to a time long ago and every road has its own idea of the elevation and direction that humans should walk. The daytime bazaar is like a scene out of Disney’s Aladdin where everybody is “my friend” and everybody has something pretty to sell to a pretty girl.

The smell of herbs and pastries fill the Muslim Quarter, where a non-Muslim cannot venture too far without being stopped and told to return. The sounds of people gathering at the Western Wall on Shabbat (the Seventh Day of rest in Judaism) fill the Jewish Quarter every Friday. The sight of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter, which was once that of Jesus’ crucifixion, is headquarters to the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem.

The smell of herbs and pastries fill the Muslim Quarter, where a non-Muslim cannot venture too far without being stopped and told to return. The sounds of people gathering at the Western Wall on Shabbat (the Seventh Day of rest in Judaism) fill the Jewish Quarter every Friday. The sight of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter, which was once that of Jesus’ crucifixion, is headquarters to the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem.

The story of how I ended up in the Old City doesn’t go back quite as far as the presence of Armenians in Jerusalem, which predates Christianity. It was five years ago in my Armenian history class at UCLA that Professor Richard Hovannisian described the age-old tradition of Armenian pilgrims in the Armenian Quarter. It was then I started dreaming about the day I would embark on a solitary journey to the historical city.

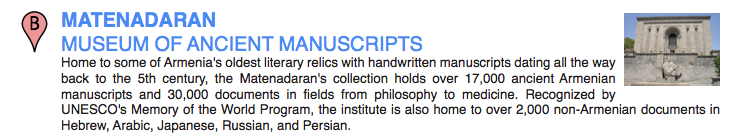

Out of the four quarters, the Armenian is the smallest and the most walled off. Home to roughly 500 Armenians, it makes up one-sixth of the city. Armenian cafes, taverns, restaurants and souvenir shops selling famous ceramics are found on streets with Armenian names written in Arabic and Hebrew scripts.

For hundreds of years, Christian pilgrims have made journeys to the Holy Land, taking with them one souvenir:

“What kind of tattoo do you want?” Wassim Razzouk, my Harley-riding tattoo-artist asked.

“Give me what you give Armenian pilgrims,” I said hoping he’d know what I was talking about.

Turns out he knew exactly what I was talking about. The year before, he had tattooed seven Armenians from New York, all around my age. In fact, one of the first tattoos done by Wassim’s ancestors was one of Armenian letters dating back to 1749. That was around the time his Coptic Christian family moved from Egypt to Jerusalem, where they have tattooed Christian pilgrims for the past 250 years.

Turns out he knew exactly what I was talking about. The year before, he had tattooed seven Armenians from New York, all around my age. In fact, one of the first tattoos done by Wassim’s ancestors was one of Armenian letters dating back to 1749. That was around the time his Coptic Christian family moved from Egypt to Jerusalem, where they have tattooed Christian pilgrims for the past 250 years.

My uncle hoped to be one of those pilgrims. As the ink settled into my arm, I thought about how he dreamed to one day be at the very spot I was. And it dawned on me that it had been exactly four years to the day since his passing. But if there were ever a time and place where surrealism reigns, it would be the Old City. Because here, there is no sense of time, no separation of modern and ancient. The religious air has pervaded throughout the centuries and permeates every corner of the old town.

I escaped into the Armenian Quarter where the St. James monastery has stood since the 14th century. The church that provided refuge to Armenians during the Genocide, now provided refuge to me from a world where the struggle for cultural survival follows each generation. The familiarity of the Priest’s voice echoing within the church walls resonated with my soul. I walked out of the ornate room and rounded the corner to a courtyard surrounded by Armenian dwellings. That’s where I saw the majestic cross-stone statue standing in front of me like an epiphany.

“I have no idea what it is like to be an Armenian,” William Saroyan wrote in his short story Seventy Thousand Assyrians. “I have a faint idea of what it is like to be alive.”

And looking down on the ink on my right forearm, I smiled to myself.

Yerevan. The Carousel City.

By: Vrej Haroutounian

A few months ago when I was in Yerevan, a friend and I found ourselves leisurely strolling down Abovyan Street whilst talking about our immediate experiences of the last few weeks. She turned around to me and said, “This city is kind of like a never-ending carousel, you get on at one place and you get off at another but during the whole time you are just going around and around the city.” Yerevan was a carousel and we were traversing its circuitous path as it presented us our life’s surroundings by what history had built.

Every city is mirror for and reflection of society. The city creates a backdrop to a theatrical performance, which is the life of the people interacting in it. We build the city to reflect what we would like to have as the backdrop to the story of our lives, and after the city ages she reminds us of our thoughts at the time and what scenes from our life’s play we were performing then. Even if we might forget the details, the city—in all that it is and isn’t in that moment—will forever remind us. Through its buildings, parks, streets, and movements, the city becomes the physical execution of all of our intellectual and physical expressions, as we build our ideals into our cities. We build our dreams into our city, we build our souls into the city, and then the city reflects back to us the spirit with which we created all that we did during that particular moment in time.

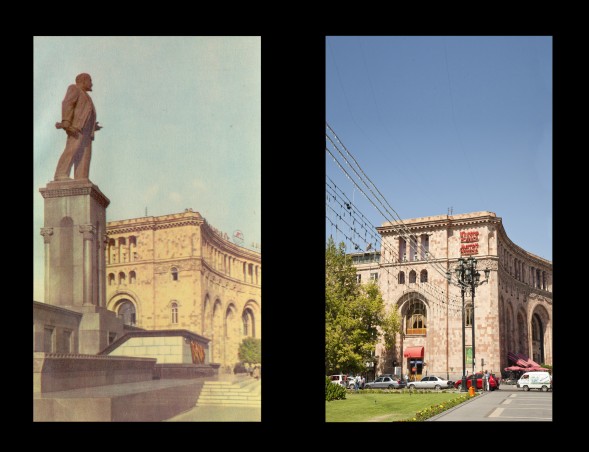

When we look at some of the streets and buildings in Yerevan they take us back to the 1940’s era of Yerevan and we start imagining how people lived then, and what clothing they wore and what books they read, how they greeted each other. When we look at the taller buildings built around the 60’s – 70’s we think about why the shift took place, we notice the change in the building design. If we look carefully enough, we can see the details in the quality of construction, we can understand why a shift happened in the material quality, why buildings went from 4 stories to 16. We start to think about why these changes took place, if the quality of construction went up that means the city was prospering if it went down, then the economy was not doing well, or maybe there was corruption, or a shift in construction material, or ideology. The city starts becoming a record of the people that built her and why they built her the way they did, as the backdrop to the theatrical performance of their lives at the time.

Then the fun begins because you are the main actor of a theatrical performance of your life story, and the backdrop is Yerevan. The year is 2012 for example. The season, summer. The scene starts with you waking up and walking down the street. Where do you get a cup of coffee? At a café in the corner of a small street? At a café that surrounds Opera that is covering what used to be a large park? Or at a friend’s house? The decision you make in the theatrical performance of your life will, over time, mirror in the urban landscape of Yerevan, because if you want that park to reappear from below that café, then you should have your coffee on the corner of a street or at a friend’s house and not deprive nature of her natural greenery by increasing the need for more cafes.

Then the fun begins because you are the main actor of a theatrical performance of your life story, and the backdrop is Yerevan. The year is 2012 for example. The season, summer. The scene starts with you waking up and walking down the street. Where do you get a cup of coffee? At a café in the corner of a small street? At a café that surrounds Opera that is covering what used to be a large park? Or at a friend’s house? The decision you make in the theatrical performance of your life will, over time, mirror in the urban landscape of Yerevan, because if you want that park to reappear from below that café, then you should have your coffee on the corner of a street or at a friend’s house and not deprive nature of her natural greenery by increasing the need for more cafes.

Then the question becomes, do we favor Cafés over Parks, do we favor street vendors over Super Markets, do we favor public transportation or the dream of each having a Range Rover? What do we want the backdrop of life to look like? The city will reflect in physical form, each and every choice we make in how we choose to live. When we choose the Range Rover, the streets will get wider over time and the public transportation suffers as congestion increases. By choosing to shop at commercialized supermarkets, street vending will become obsolete, barring access to more natural, non-synthetic food, and yet goods will be conveniently and easily accessible in wholesale at these markets, ready to be purchased and placed inside those very Range Rovers we drive.

We are the architects of our surroundings. Architecture is a democratic process that we all engage in everyday. If we want to live in a pedestrian-friendly Yerevan then we have to incorporate walking into our everyday lives. If we want to have street vendors, then we need to support them with that extra effort of walking to where they are. Walking twenty more minutes to get our groceries would in turn be great exercise as well.

Next time you wake up in Yerevan think to yourself, “I am in a unique city with a great backdrop that was created by a very unique people over the last hundreds of years as the backdrop for the theatrical performance of my life that is going to take place today. What is my performance going to be as an actor walking through that set and how might my actions and decisions impact the city?” Imagine yourself as an actor putting on a performance as you walk through this great city, read her history with your senses, and write her present and future with your actions.