Interview with Dr. Rubina Peroomian: The Power of The Pen

Haytoug: Armenians have long took pride in education and having an alphabet that is now over 1,600 years old. Given this legacy, how big of a role would you say the written word and literature has actually had on shaping the destiny and identity of the Armenian people?

Rubina Peroomian: Yes, we are proud of our culture, our heritage and our 1600-year-old alphabet. We are proud of the rich literary output that made the fifth century the Golden Age and the tenth and eleventh centuries the Silver Age of Armenian literature.

Yes, education has always been one of the key values upheld in Armenian families. But this consciousness was germinated, expounded and disseminated by the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance movement which was launched to enlighten and educate the Armenian masses, disseminate religious and cultural values, and propagate ideas of modernity. Before then, these values were esteemed and perpetuated by a relatively small class of men and women—which included the clergy, the ruling class, the nobility and the intellectuals—while the masses lived in ignorance and poverty under the yoke of foreign domination, deprived of basic human rights.

What shaped the destiny and the identity of the Armenian people, in other words, what sustained their survival throughout their turbulent history, was their devotion to Christianity in the midst of the encroaching Muslim world and a subconscious effort to maintain and perpetuate their ethnic origin, traditions and language. An influential factor here may have been the spoken word and not the written word or literature.

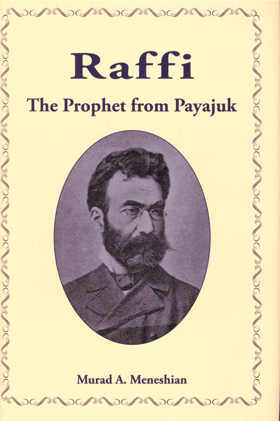

H: It is often said that the cultural renaissance of the Zartonk (Awakening) period of the 19th century gave birth to the Armenian revolutionary movement. In what ways exactly did writers like Mikael Nalbandyan, Khatchadour Abovian, Raffi and others spur Armenians to stand up for their liberation? Weren’t the material conditions experienced by Armenians in the Ottoman Empire alone enough to make them want to resist their oppression?

R.P.: The political awakening was the final phase of the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance which began with an Enlightenment movement, the establishment of a network of modern schools, the periodical press, and the modernization of the language with the replacement of Grabar (which was unintelligible to the masses) by two literary languages closer to the dominant vernaculars. Through these vehicles the Armenian intelligentsia were able to propagate the Renaissance ideology which was, in essence, the aspiration to live the life that all humankind deserved to live. And the model, or the source of inspiration, was not so much the European example but the glory of the Armenian past, drenched with an insatiable love of liberty and justice and bolstered by a rich culture that Armenians can be proud of. The Armenian masses needed to become conscious of their own deplorable situation before they were able to aspire to a better future. It was during this period that the written word and the literature created by the Renaissance writers, some of whom you mentioned, assumed the role of reshaping the Armenian identity which had been buried in obscurity and the darkness of centuries of subjugation. This literature cultivated the Armenians’ will to stand up and fight for their rights and take their destiny into their own hands. Call it tendentious or committed literature if you will, let some literary critics campaign against it, but the literature of the Zartonk period did the job. This literature can be considered the realization of the theory of “reflect and control,” to use Melvin J. Vincent’s expression. It presented Armenian life as it was in its ugliest aspects, and at the same time it propagated and cultivated what was desirable, what was worth fighting for, in the reader’s mind. In other words, the Renaissance artists not only held up a mirror to reflect life as it was, they presented a model of what it should be. These models created characters, heroes of national dimensions who acquired flesh and blood in the forthcoming national struggle for liberation.

R.P.: The political awakening was the final phase of the nineteenth-century Armenian Renaissance which began with an Enlightenment movement, the establishment of a network of modern schools, the periodical press, and the modernization of the language with the replacement of Grabar (which was unintelligible to the masses) by two literary languages closer to the dominant vernaculars. Through these vehicles the Armenian intelligentsia were able to propagate the Renaissance ideology which was, in essence, the aspiration to live the life that all humankind deserved to live. And the model, or the source of inspiration, was not so much the European example but the glory of the Armenian past, drenched with an insatiable love of liberty and justice and bolstered by a rich culture that Armenians can be proud of. The Armenian masses needed to become conscious of their own deplorable situation before they were able to aspire to a better future. It was during this period that the written word and the literature created by the Renaissance writers, some of whom you mentioned, assumed the role of reshaping the Armenian identity which had been buried in obscurity and the darkness of centuries of subjugation. This literature cultivated the Armenians’ will to stand up and fight for their rights and take their destiny into their own hands. Call it tendentious or committed literature if you will, let some literary critics campaign against it, but the literature of the Zartonk period did the job. This literature can be considered the realization of the theory of “reflect and control,” to use Melvin J. Vincent’s expression. It presented Armenian life as it was in its ugliest aspects, and at the same time it propagated and cultivated what was desirable, what was worth fighting for, in the reader’s mind. In other words, the Renaissance artists not only held up a mirror to reflect life as it was, they presented a model of what it should be. These models created characters, heroes of national dimensions who acquired flesh and blood in the forthcoming national struggle for liberation.

The revolutionary movement was a byproduct of the Renaissance, as was the formation of the Armenian political parties (1885-90). It was not widespread, however. In fact, it was launched by a few who believed in the importance of self-defense as a means toward national liberation, and its followers were the few with arms-in-hand who were weary of the repression, the persecution, the Turkish and Kurdish assaults, the looting, rape and kidnapping that were rampant in the Ottoman Empire. It took years of struggle to move the masses—who were submerged in darkness and had adapted to their lot—to sensitize them to their own predicament and influence them to see the possibility of changing the status quo.

H: In many of the novels, poems, songs, and literature of the Zartonk period, we find a common emphasis on the theme of youth and the importance of passing on values of freedom and justice to the younger generation. Why was there such a strong emphasis on the youth by writers back then?

R.P.: The Renaissance movement began with the enlightenment campaign in a newly established network of schools, that is, the education of the youth. If the Armenian Zartonk ideology called for a change in the destiny of the nation and for the destitute masses to once again become a nation with goals and aspirations, the young generation had to be prepared to take on the commitment and lead the way. The significance of the power of youth activism can be seen throughout the history of mankind. “Youth are the future”— the statement is old and worn but it is true. An example close to our life in America, known to all, is that of the Mexican American Youth Movement of the 1960s and the changes brought about by the relentless activism of Chicano youth. In the Armenian reality of the early nineteenth century, the imaginary characters that Renaissance writers created and hoped to see materialize in real life were young individuals with a profound consciousness of the plight of the nation and an unwavering commitment to bringing change. And we have seen the burgeoning of these young heroes thrusting forward even when their lives were at stake.

H: You’ve written a great deal about literary responses in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide. What can such literature convey to us about the Genocide that historical facts or oral history cannot?

R.P.: Your question leads to the essence of my work as a genocide scholar whose field of research is artistic literature with the Genocide at its core. For many long years now, I have studied the literature of atrocity—to use Lawrence Langer’s terminology— in order to understand the human dimension of this colossal crime which today is called the Armenian Genocide. My writings expose the last cries of the victims of the great injustice that has still not been redressed. They speak of the survivors’ perceptions of the calamity and how their tragic experience has indelibly impacted their psyches and become a debilitating influence in their lives; how harrowing images of their past experience, triggered by visual, aural, olfactory or other associations, revisit them in their waking hours, and return in their sleep when the unconscious overrides conscious control to push dormant images to the surface.

In my reading and explication of these artistic creations—memoirs, auto-biographical novels and other genres of genocide literature—I have tried to illuminate a dark corner of the horrendous landscape of the Armenian Genocide which will never be completely known, and the boundless sea of personal and collective pain and suffering that will never be fully recognized. Although I provide historical background to the places and events under discussion in my work, I never attempt to prove the veracity of the Genocide. It is there as the point of departure, as the source of the breach in Armenian life and all the paradigms of responses to historical catastrophes, and the source of the new reality which is life in the diaspora.

Literary responses to the collective catastrophe reflect the reality perceived by the writers. These writings are the truth as it happened. The reader relates to that truth and absorbs it like no other document or fact sheet.  Allow me to quote a passage from my most recent book which discusses the same issue and demonstrates the intrinsic value of Genocide fiction and symbolic poetry “as elucidators of universal truths that lie at the roots of historical facts, putting inconceivable realities into human perspective… assisting readers to grasp the meaning of a historical event.”

Allow me to quote a passage from my most recent book which discusses the same issue and demonstrates the intrinsic value of Genocide fiction and symbolic poetry “as elucidators of universal truths that lie at the roots of historical facts, putting inconceivable realities into human perspective… assisting readers to grasp the meaning of a historical event.”

Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, a Jewish Holocaust scholar, once declared that “The Holocaust has already engendered more historical research than any single event in Jewish history, but I have no doubt whatsoever that its image is being shaped, not at the historian’s avail, but in the novelist’s crucible.” Indeed, it is the artist’s creative power that can capture the unthinkable horrors of genocide and bring them within the scope of the reader’s imagination. That is the power of the pen.

H: Over recent years, there has been a small but growing number of Turks who have begun questioning the denialist narrative of Turkey regarding the Genocide. A significant proportion of these individuals have been writers, poets, novelists, and literary figures such as Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak. What role do you feel literature is playing in the development of a critical voice in Turkey on the Genocide?

R.P.: There is certainly an ongoing metamorphosis at the intellectual level in Turkey, a change in perceptions of the Turkish past, to the extent of questioning the official Turkish narrative. And this is not so much a matter of confronting the denial of the Armenian Genocide, but of challenging the Republican narrative based on the idealization of the founders of the Republic— many of whom were important political figures during the late Ottoman period and, thus, perpetrators of the Armenian massacres—and of questioning the denial of the multiethnic, multireligious and multilingual makeup of Turkey. These intellectuals are in quest of their own true identity. They are struggling for the democratization of the republic and for the lifting of censorship on intellectual endeavors. Their influence on public opinion outside Istanbul is minimal, I would say, but change is in the making. It is undeniable. And the effect of artistic literature such as Orhan Pamuk’s Snow, Elif Shafak’s The Bastard of Istanbul, Fethiye Çetin’s My Grandmother, Kemal Yalçın’s You Rejoice my Heart, Mehmet Uzun’s Pomegranate Flowers, and other works are gradually being felt. Of course, it is also undeniable that these artistic creations or memoirs are supported and reinforced by historical findings, by the books, exposés and discourses of historians, scholars and human rights activists such as Taner Akçam, Ayse Gül Altınay, Fatma Müge Göçek, Osman Köker, Hülya Adak, Ayse Günaysu and others.

H: What are your thoughts on the rapid spread of modern technologies and the popular phenomena of social media today? Can these platforms serve as useful tools for a modern, 21st century Zartonk and revival of Armenian literature?

R.P.: The spread of modern technology and the popularity of social media can be useful and harmful at the same time. The positive impact of this medium, so familiar to the young generation, is undeniable if used with a controlled effort, such as initiating monitored discussions, disseminating ideas, promoting understanding and support for the Armenian Cause and literature. It is possible today to send out information, organize fan clubs and groups, or rally support for or against an Armenian related piece of news in a matter of hours through Facebook and the like.

However, the downside of social media is that it does not lend itself to serious literature and is mostly a space for quick notes, observations, and so on. As for casual online discussions, they can go out of control and boil down to useless chat. A revival in literature in Armenian? I doubt this. A unified easily accessible medium in cyberspace in Armenian is yet to be developed.

H: Do you have any upcoming projects or research you can tell our readers about?

R.P.: Yes, of course, and thank you for this question. My third book on Armenian Genocide literature was published in March this year, and I am already working on the next volume to complete my interpretation of the perceptions of the Genocide by Diasporan Armenian survivor writers of the first, second and third generations.

Meanwhile, I have been working on the project of teaching the Armenian Genocide to Armenian students in K-12, initiated years ago by the Board of Regents of Prelacy Armenian Schools. I have perfected the project, adding missing materials and lesson plans for each age group, and I introduced it at the biennial educational conference sponsored by the Ministry of Sciences and Education of the Republic of Armenia. Because of the enthusiastic reception of the project by Armenian teachers from all over the world, the Ministry of Education agreed to adopt the project, prepare an online version of it and offer it for use by all interested parties, free of charge. It is now posted on the Ministry’s website, at www.spyurq.dasagirq.am, to be exact.

In participating in the 2012 conference this summer, my goal will be to publicize the project and work for its worldwide distribution and dissemination so that every Armenian student, wherever he or she may be, will have the chance to learn about this important turning point in the history of the Armenian people, through age-appropriate materials, tools and methodologies.

I want to see Armenian youth armed with the knowledge of history and of Armenian national rights, logically, without emotional impulse. I want to see Armenian youth properly educated to become committed soldiers of Armenian national aspirations.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!