Recollecting Rwanda: A Lesson in Forgiveness and Respect

I arrived in Kigali, Rwanda on August 9, 2010: election day. The entire country was in the midst of celebrating their opportunity to re-elect Paul Kagame, a national hero since since leading the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) to end the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Kigali–the nation’s capital–was covered in streamers that matched the Rwandan flag and every voting center erupted with music, laughter and dance. Shortly after settling into my home in the Kabeza neighborhood, I was invited into the playground of a nearby school-turned-polling-place by a middle-aged man who had just submitted his ballot.

“Come, come!” he said. “Please, be with us today. This is a celebration!”

I had never seen anything like this before–not even when U.S. President Barack Obama was being elected. Children danced gleefully as their parents waited in line to vote, each wearing t-shirts with Kagame’s portrait. Upbeat Rwandan pop music piped into the air from massive speakers. Elderly Rwandan men and women sat under shady trees, energetically discussing the historical moment they were witnessing. Every single person was smiling from ear-to-ear with pride. Had I not already learned of Rwanda’s history, I would have never guessed that a mere 16 years prior to that moment, Rwanda was a living hell devoured by the pitch darkness of a genocide that claimed the lives of nearly one million of its people.

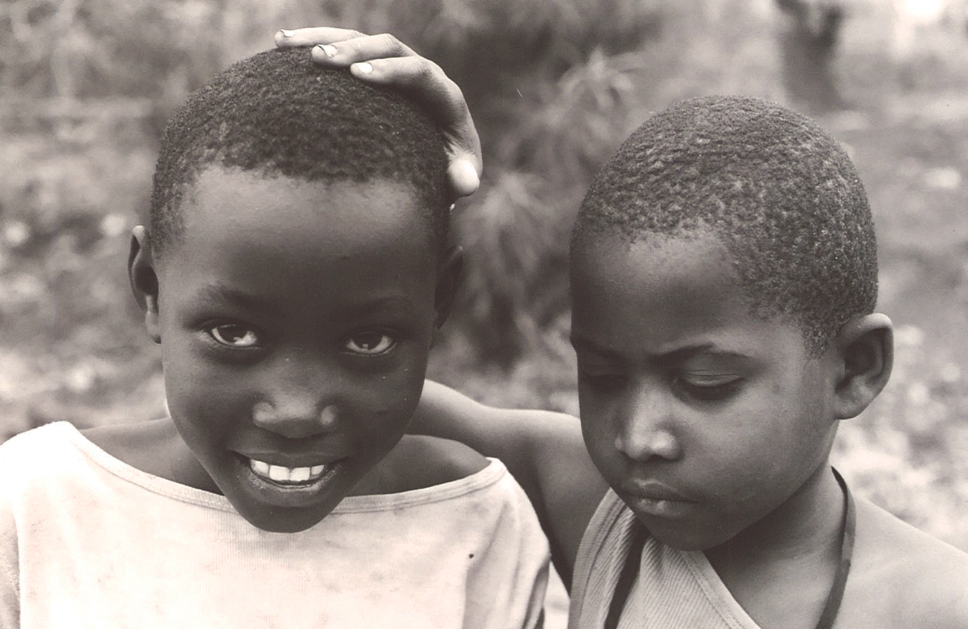

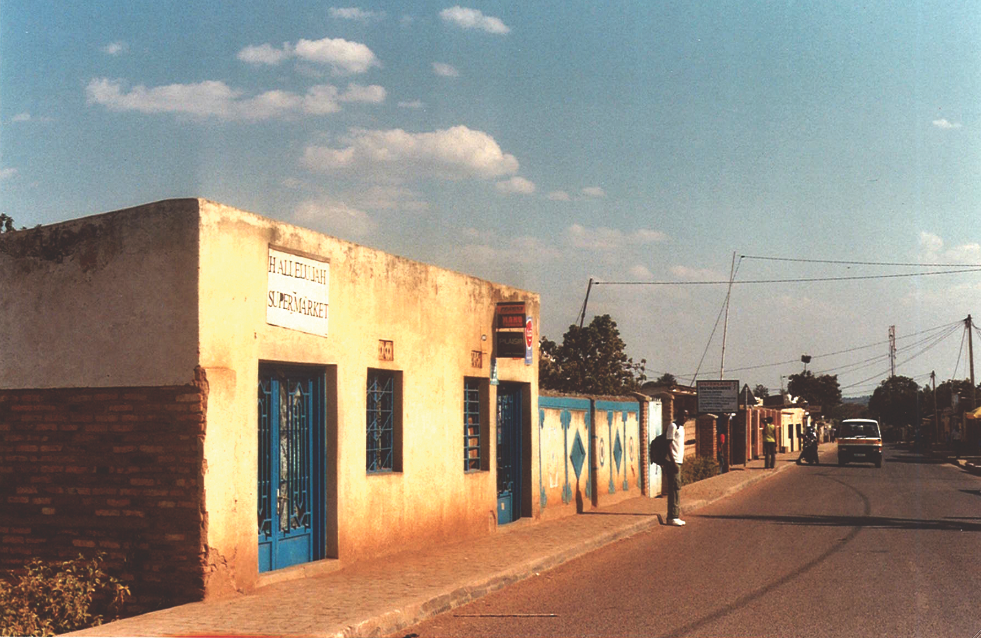

I re-experienced this pattern of revelation over and over again throughout the month I spent in Kigali. Each day, I would encounter a new aspect of Rwandan culture that would leave me in awe; I had never met such openhearted people in my life. Perfect strangers on the bus would take another passenger’s child to sit on their own lap if there was a shortage of seats, the elderly were looked upon like national treasures, children played freely outside with no fear of kidnapping, women walked side-by-side with men in the evenings with no fear of rape or petty theft, shop owners offered their own cell phones to clients if the power had gone out…and all this in addition to the kindness shown to me as a guest in their country. Each time I observed or experienced such moments, I would immediately go back to the same question: how did these people exist in such harmony, when less than twenty years ago they were at each others throats?

I re-experienced this pattern of revelation over and over again throughout the month I spent in Kigali. Each day, I would encounter a new aspect of Rwandan culture that would leave me in awe; I had never met such openhearted people in my life. Perfect strangers on the bus would take another passenger’s child to sit on their own lap if there was a shortage of seats, the elderly were looked upon like national treasures, children played freely outside with no fear of kidnapping, women walked side-by-side with men in the evenings with no fear of rape or petty theft, shop owners offered their own cell phones to clients if the power had gone out…and all this in addition to the kindness shown to me as a guest in their country. Each time I observed or experienced such moments, I would immediately go back to the same question: how did these people exist in such harmony, when less than twenty years ago they were at each others throats?

I traveled to Rwanda to teach a month-long photography course to a group of men and women in Kigali who needed vocational skills and didn’t have access to arts education or equipment. Several of my students were orphaned in the genocide, and almost all were old enough to have distinct memories of what happened in 1994. I didn’t learn any of this until a handful of my students took me to the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, though, because there is a general, unspoken consensus amongst Rwandans to actively resist discussion about the genocide; in fact, I was told before my arrival that bringing up the topic of the genocide was considered highly offensive and disrespectful. Until our visit to the Memorial, I had no way of knowing what my students, let alone everyone else in Rwanda, had experienced during and after the genocide unless I read it in a book or on the Internet. I didn’t encounter anything throughout my time in Kigali that referred to the genocide–everything had been suppressed as a means of quickly forgiving one another and moving on, in order to be able to focus on Rwanda’s future and rapid development.

When we were at the Memorial, one of my students finally opened up about losing his entire family in the genocide. He said that it was hard for him to go inside the museum and relive what happened, but that he had no anger in him. He had forgiven the people who killed his siblings and parents and did not harbor hatred towards them. This ideation was remarkable to me. It was so difficult to reconcile this reality with my frame of reference: my experience in the Armenian diaspora, where any talk of forgiving the Ottoman perpetrators (and their descendants) of the Armenian genocide is practically non-existent.

When we were at the Memorial, one of my students finally opened up about losing his entire family in the genocide. He said that it was hard for him to go inside the museum and relive what happened, but that he had no anger in him. He had forgiven the people who killed his siblings and parents and did not harbor hatred towards them. This ideation was remarkable to me. It was so difficult to reconcile this reality with my frame of reference: my experience in the Armenian diaspora, where any talk of forgiving the Ottoman perpetrators (and their descendants) of the Armenian genocide is practically non-existent.

I learned from an exhibit at the Memorial that many accused killers in the Rwandan genocide have since been released back into society, simply because the families of their victims have forgiven them (as dictated by Gacaca, a tribal-based justice system instituted in the wake of the genocide). As a result, both victims and perpetrators of the genocide are now once again living side by side. Although they are divided by their respective experiences, they are united in thought: that to kill one another is wrong, that the genocide was a bloody lesson in peace and understanding and that the only way for Rwanda to move on and flourish is if each and every Rwandan does their part to move on individually. Of course, this is a double-edged sword: countless survivors of the genocide are now living with severe trauma-related disorders, psychological issues and depression but are actively participating in this repression that will inevitably make their mental conditions worsen. Yet for the people of Rwanda, this seemed to be a worthy sacrifice; to hold back their personal healing for the sake of not tainting the new generation with the disunion, hate and anger that nearly shattered Rwanda just 16 years ago. The result, from what I described at the beginning of this narrative, is a country ruled by peace, love, unity, respect and unadulterated selflessness.

Anahid Y is a 21-year-old student at Occidental College in Los Angeles, where she is studying comparative literature and film theory. She chronicled her experience in Rwanda on her blog, recollectingrwanda.tumblr.com. Her students’ photography will be exhibited alongside her own later this year on the Occidental campus.

Facts about the Rwandan Genocide:

- The Rwandan genocide is officially noted to have started on April 6, 1994 after the assassination of then-president Juvénal Habyarimana; it lasted approximately 10 months and 800,000-1,000,000 people were killed.

- Tensions between the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi ethnic groups had been intensifying throughout the 1900s, culminating in the Hutu-dominated government of the 1990s declaring total cleansing of Rwanda’s Tutsi population. The distinctions that separated the Hutus from the Tutsis were minimal and mostly class-based; they gained prominence at the behest of Belgian and German colonists in the first half of the twentieth century, who then gave privileges to the Tutsis that immediately separated them from the Hutu majority. It was only a matter of time, then, until the Hutus retaliated. By 1962, however, colonization was over and the only people left to weather Hutu anger were the Tutsis themselves.

- Thousands of Tutsis had been living as refugees in neighboring Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), among other countries, for decades at the time of the genocide and so were unharmed. Once the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by current President Paul Kagame, ended the genocide, many of these diasporans repatriated to Rwanda and repopulated the country–physically about the size of the U.S. state of Maryland–thus contributing to its current population of nearly 9 million.

- Since the genocide, ethnic terminology has been totally eliminated in Rwanda; any mention of the Hutu and Tutsi distinction is considered highly offensive, and people identify themselves–both personally and on official documents–only as Rwandan.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!